For decades, campus planners, facilities managers and space administrators have been trying to manage building spaces in the most efficient way possible. Although there have been some minor success stories, most struggle to use space well. This is due to a lack of interest and understanding of the benefits embraced by those using the space. Planners have built utilization guidelines, utilization metrics, architectural standards, scheduling algorithms, and the list goes on. Yet, the expansion trend continues. The “black hole” of underfunded deferred renewal and increased operational costs continues to grow. Captain James T. Kirk might be correct when he said, “Space—the final frontier.”

To advance efforts in utilizing space better, developing sound policies for the management and use of space, creating appropriate architectural standards to support program needs, and employing strategic scheduling programs are critical. But more important may be the opportunity to change the culture and the attitude towards our campus spaces. Space is no longer only a facilities issue. It is a university-wide, programmatic issue and must be treated as such. Let’s ask ourselves some key questions, look at things from a few perspectives, and explore a variety of considerations that may help campuses do more with less.

Space as an Influencer

Start with the fact that space is literally everywhere (no pun intended). Campus spaces, whether positively or negatively, impact an entangled web of campus operations that go far beyond what many think of as a typical space issue. Does the program have enough space? We tend to spend a lot of time asking that question, doing space studies, creating projects, completing renovations, and reacting to space requests. What about a space’s entanglement and the fact that every time space changes it impacts the following—and more?

- University insurance rates

- Deferred campus renewal (maintenance)

- Operating budgets (departmental, facilities, utilities)

- Sustainability considerations

- University rankings

- Potential student perceptions

- Academic and learning delivery

- Program accreditation

- Research opportunities

- Diversity, equity, and inclusion

- Health and wellness

- Living arrangements

- Collaborations

- Support program change.

Then add another layer of entanglements. Space is also:

- Slow changing and hard to adapt

- Extremely expensive

- Hard to account for

- Difficult to provide incentives for good use

- Multi-dimensional (quantity, quality, design, location, technology)

- Outside and underground our buildings.

If universities continue to consider just how much space is entangled at every level, eventually space management practices will advance to be proactive and of added value. Assuring our spaces can continually align with the diverse program needs of our institutions begins with our understanding of the importance of sound and strategic space management practices.

Perceptions and Facts

Regardless of how space is managed or funded, the true cost of running a program must include the facilities requirements (space costs).

Space is free, correct? Let us face the fact that 98% of campus users think space is free. It’s the root cause of so many of our space deficiencies. Users are typically not accountable for the space in which they reside. The way universities are organized and the accounting for building operational costs shield users from understanding the true costs associated with underutilized spaces. In most cases, space is a centrally funded resource one simply asks to use.

True, some campuses have measures to assure that the space requests are justifiable, but typically programs fight for as much space as they can get because, to them, it is a free resource. If programs had to pay for the space they used, you would see an immediate improvement in utilization. That said, a budget reform, which has been explored with mixed results, is not necessary. But changing the perception is a must. Regardless of how space is managed or funded, the true cost of running a program must include the facilities requirements (space costs).

A final note on this is that the need for space is time dependent. Say in Year 1, it is decided/justified for a program to get more space. What happens in Year 5? Year 10? Institutions must continually evaluate all programs’ space needs and do so based on how individual programs operate and their strategic needs, not on what is requested. In addition to regularly reevaluating a program’s need for space, it is important to indicate the costs of that space so that all parties can see the impact on a university’s overall operating budget. For reference, a typical office carries associated costs. Also consider expensive research and instructional spaces that can cost 4–5 times that of offices.

Average office costs

Capital investment $50,000–$60,000

Annual operating costs $1,500

Annual renewal budget $1,250

Once costs are transparent, the next question is who owns the space? There are any number of correct answers to this question, but the typical incorrect answer is: the occupant. That said, the occupant typically is defining the needs and demands on space but they are not typically paying for it. Establishing a level of ownership and accountability for space is important regardless of the accounting system. Good decisions regarding space use and allocation must consider the stewards’ responsibility to the actual owners whether it is the State, Regents, or even a third party.

Even though space or a set of rooms is a subset of a building, space and buildings must be evaluated separately. Institutions do a pretty good job evaluating and understanding the quality of buildings and the systems that support them. Facilities condition assessments and other evaluation tools have been developed over the years to give us a good understanding of the quality of a building. That does not mean the space within the building supports its programs. Too many times, a facility’s condition index may indicate a building’s value is diminishing; however, the value may improve by simply changing its use. Most facility condition assessments do not consider program value.

It is important to balance both building and space assessments before making long-term decisions about a facility. A simple example is a 30-year-old research laboratory building costing $20 per square foot to operate that has a deferred renewal cost of $30 million. Changed to open office environments can reduce its operating cost to $9 per square foot and lower its deferred maintenance to $20 million with minor system modifications. This is due to the simplified requirements to support a new use.

Utilization vs. Optimization

Utilization

Universities have spent decades evaluating how well a space is utilized by doing studies based on how often a space is scheduled or used. It is a one-dimensional evaluation of room use with the following characteristics:

- Looks at a specific point in time

- Addresses academic space

- Considers a single, specific, space type

- Is short lived because use changes the next semester

- Does not typically include occupancy (fill rate).

Most institutions perform utilization studies on instructional classrooms and laboratories, but not much else. This is ironic considering that classrooms and laboratories make up less than half of the office space on most campuses and are mission critical spaces. Office spaces, on the other hand, are the poorest used rooms on any campus and are of little value to student success.

Ask yourself, “Why do we keep spending an extraordinary amount of time, funds, and energy trying to use our instructional spaces one more hour per week but ignore the fact our offices are typically empty?” It is time for campuses to focus on the real space utilization culprit. The timing is perfect thanks to the recent pandemic and proof that office functions are not location dependent. Hybrid and remote work can have a powerful positive impact on improved space use.

Optimization

Space optimization is a multi-dimensional approach to space use and evaluations. It not only considers the traditional utilization strategies, but also considers a variety of other assets of a space. Optimizing space considers the ability of the space to support multiple and diverse functions, multiple schedules, a variety of stakeholders, and the associated costs. The multi-dimensional approach considers a space’s ability to:

- Serve its purpose most efficiently

- Be multipurpose

- Adapt and be flexible

- Support program needs

- Be cost effective and lower the total cost of ownership.

In addition, a multi-approach should include the following:

- Evaluation of the annual operational costs.

- Understanding the long-term renewal costs.

- Determination of the number of programs the space can support (sharing).

An institutional goal should be to transition from the traditional utilization reports and metrics to that of an optimization framework. Many of the variables associated with optimization stem from our academic programs. This requires a strategic marriage between facilities and space management professionals with the academic community, providing a perfect opportunity to build a collaboration and trust.

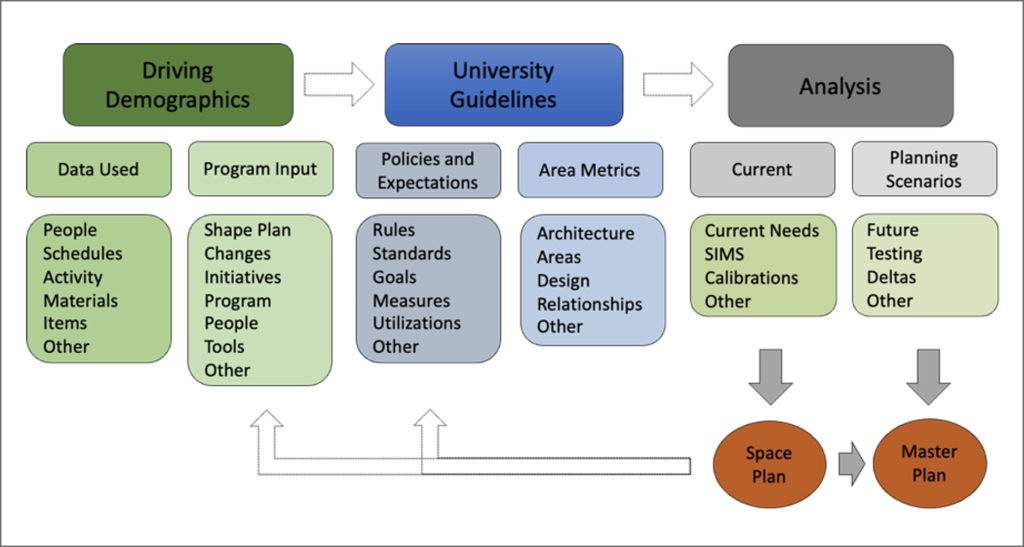

Optimizing space on a campus requires strategies and tools that allow the institution to test a variety of options relative to space use. One consideration is to create a space model that allows an institution to continually evaluate its space needs based on any number of operating or planning scenarios. Models can incorporate many, if not all, of the variables to look at space optimization. Models can be basic or complicated depending on the institution’s needs; either provides the ability to evaluate and test a variety of options to optimize space use. An added value to modeling is, if developed in the right way, it can establish academic, administrative, and facilities partnerships that are priceless.

Modeling

-

- Builds collaboration among all campus units.

- Allows programs to create planning metrics so users define the options and needs.

- Is used for master planning, programming, and space management.

- Assures analysis and studies are data driven and not personality driven.

- Is dynamic and everchanging.

- Provides the opportunity to plan and test a variety of planning scenarios.

- Supports all levels of planning.

Optimization

-

- Requires a programmatic and facilities marriage.

- Builds on common objectives/expectations.

- Is supported and backed by campus leadership.

- Assumes shared use whenever possible.

- Gains institutional commitment and provides incentive to a larger audience.

- Supports multi-purpose uses of space.

Figure 1: Space Modeling Approach

Program Value

Facilities organizations have staff with expertise to take care of the buildings and their systems, campus grounds, and the utility infrastructure. They typically do not manage what people do in the space within the buildings. This expertise resides in the hundreds of programs that use campus spaces. Something we must ask ourselves is why do most campuses have space managers within facilities management.

It would be prudent for all our campuses to figure out how to engage programs in the appropriate way to take advantage of each program’s expertise without setting expectations that cannot be met. There are a handful of questions that may lead us to new philosophies and approaches in space planning and management practices:

How does an institution know is spaces really work for their occupants (programs)?

How does an institution know is spaces really work for their occupants (programs)?- How does an institution continually evaluate and align space with program needs?

- How much are you willing to let academics steer the boat?

- When does “high utilization” fail?

- What is acceptable emptiness?

- Who leads future space plans?

- Do you analyze the quality of space?

- How many times could you have changed the function to reduce costs?

The above are basic thoughts (there are more) that will likely challenge current work practices. The key is making sure there is a proactive, strategic, and data driven approach to space practices. How does one translate the strategic planning objectives into space action? It is imperative that users help create the tools, processes, policies, and needs in a justifiable way. It is the only way to manage the diverse variety of operations associated with academics, research, student life, athletics, and all support and service units.

Establishing successful ways to assure how our space aligns with our program needs is difficult. It takes time and is challenging. Advanced space planning and management requires cultural adaptation that will improve collaborations between all units. Campus planning and facilities units will earn well deserved respect for their expertise. You will improve the quality of institutional buildings, while “rightsizing” space, and saving millions of dollars annually—all because of a more comprehensive approach to space planning and management. Space planning and management needs to be a university priority, not a facilities priority.

Space and the Master Plan

If there’s one thing I could change before my career ended, it would be to convince campuses to look at their master planning process and challenge how the long-term planning drives capital development. Transforming a stagnant, architecturally driven approach into a dynamic, flexible, and operating approach should be a strategic shift in planning philosophies. Although this article will not address the master planning issues, one should acknowledge the facts that 1) space drives 90% of facilities plans and 2) plans need to continuously adapt.

First, consider space as at least a three-dimensional creature. Most institutions understand space related to campus buildings, but what about outside space and the underground space critical to the utility infrastructure? Doesn’t a master planning process need to evaluate, plan for, and manage all these spaces together in a comprehensive way? Some argue there is even the fourth dimension you cannot see or touch, this being sight lines for technology, bandwidth, and even overarching campus and community policy.

Now consider the fact that space not only consists of the amount or area a program needs, but the quality of the space, the type or function within the space, and its location. Overlay these descriptors over the four dimensions and you have a complex algorithm the makes up most of your master planning challenges. Theoretically, master planning becomes a mega-space plan with a variety of planning scenarios.

Future Considerations and Embracing Change

Think about the future not as a list of specific improvements, but preparing, embracing, and supporting a cultural shift relative to the values associated with space planning and management. The recent challenges our universities have experienced during and post-COVID have enlightened our leaders to the value and importance of sound space planning and management practices. It is the perfect time to challenge our traditional ways and advance more proactive and collaborative practices. Specifically, it is time to transform our service-oriented mind set to a more strategic approach—one that places the importance of our spaces and physical environments at the forefront of our institution’s planning efforts.

Consider space entanglement not as a series of knots, but as numerous pathways or opportunities we must explore to improve planning. More importantly, it’s time for our physical environment (facilities, site, and infrastructure) to be at the leadership table, treated as equally important as our academic programs. Some approaches already proven to be successful are to:

- Be strategic, not service oriented. Change the business model from a service philosophy to a strategic approach. Become part of the leadership team that decides the future of an institution. It’s not the structural organization that is in the way, it is the operating methods. Service-oriented units rarely gain the respect they deserve regardless of how well the service is performed.

- Be sustainable by reducing the institutional building footprint. Create a plan to reduce the quantity of space on campus while increasing the quality of your space. This will also have the most dramatic impact on reducing your deferred renewal. Instead of, or in addition to, making a case for additional funds needed to maintain buildings, make a case to take the worst facilities off line.

- Manage space by engaging academic and research leadership. Establish both accountability and incentives to be prudent. Do not focus on saving facilities operating funds so more can be done. Improve to invest in academics and research. Give a large percent of any operating savings back to the programs.

- Optimize space in lieu of increasing utilization. Balance quantity, quality, location (accessibility), design, diversity in use, flexibility, and shareability. Model spaces on campus to test, plan, and evaluate on a continuous basis.

- Allow programs to lead. Establish new policies and procedures that create a collaborative approach to managing space. Academics, research, and students determine where the institution is headed. Recommend that programs have a voice and be accountable in the process.

- Increase the percentage of space centrally managed space and sharable space. Tear down the cancerous silos that academic structures and the budget process have created. Space planning and management is a collaborative process. Always look at space globally.

- Transform your traditional 10-year architectural, project-oriented, stagnant master “plan” into an integrated, ongoing, operational master planning “process.” Today’s technology allows the diverse subjects in master planning to operate independently while integrating with each other at the same time. Never use the term “living document”; it’s a fallacy.

Joe Bilotta is president and CEO of JBA Incorporated, Fort Collins, CO, providing planning and facilities management services to institutions of higher education. Since 1999 he has served on the faculty in the Planning, Design & Construction track of APPA’s Institute for Facilities Management. He can be reached at [email protected]; this is his first article for Facilities Manager.