Risk at Athletic Facilities

College athletic facility managers experienced a bomb blast outside of a football facility (Alfano, 2005), spectators injured from rushing a field (Inge, 2012), and a tornado that disrupted a basketball tournament (Sugiura, 2011). Facility managers must understand potential risks, such as fan violence, crowd control issues, natural disasters, and terrorist attacks (Hall et al., 2007a, 2007b; McCann, 2006). Facility managers need to use effective risk management strategies to reduce the risk of harm, liability (Whitley et al., 2007), a costly legal defense, or damage to an organization’s reputation (Inge, 2012).

Survey of NCAA Athletic Facility Managers

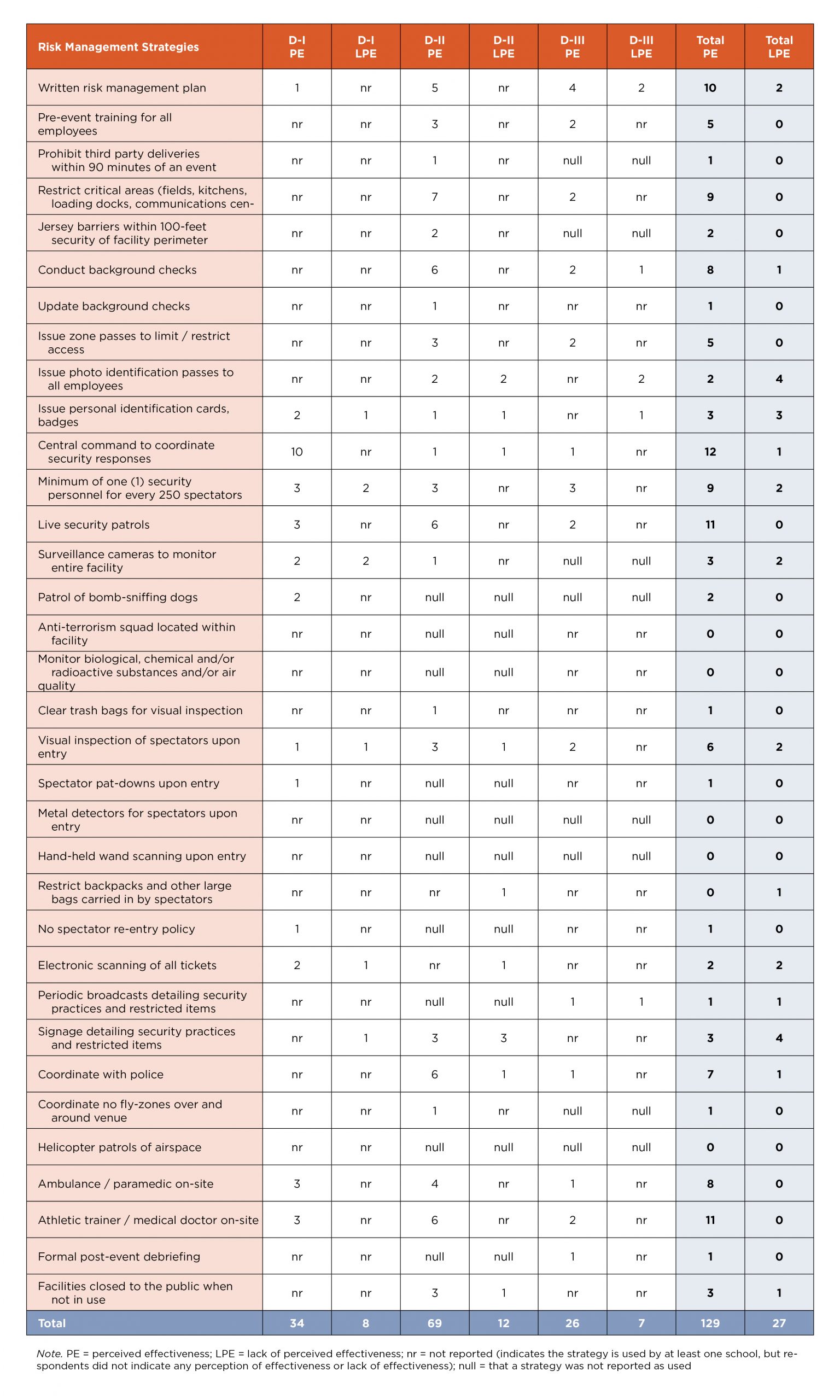

To help identify effective risk management strategies, 113 athletic facility managers across all National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) divisions (D-I, D-II, and D-III) reported in a survey on how they perceived the effectiveness of Pantera et al.’s (2003) recommended 34 risk management strategies (see Table 1). Respondents only reported on the effectiveness of those strategies they use, with effective strategies reported in the perceived effectiveness (PE) column.

To help identify effective risk management strategies, 113 athletic facility managers across all National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) divisions (D-I, D-II, and D-III) reported in a survey on how they perceived the effectiveness of Pantera et al.’s (2003) recommended 34 risk management strategies (see Table 1). Respondents only reported on the effectiveness of those strategies they use, with effective strategies reported in the perceived effectiveness (PE) column.

When respondents reported that strategies were somewhat or sometimes effective, it was documented in both the perceived effectiveness (PE) and lack of perceived effectiveness (LPE) columns. However, indicators of effectiveness cannot be generalized to be effective for all athletic facility managers or for every facility.

Risk Management Strategies Reported to Work

An athletic facility manager who perceives a risk management strategy to be effective is essentially expressing that it works. Perceptions of effectiveness may be influenced by common sense, experience and best practices, understanding patterns of human behavior, or recognizing threats. Whereas a lack of perceived effectiveness indicates that a strategy does not work, at least not every time. Most people in this study, especially those from D-II, believe that their strategies work. The most frequent successful strategies are as follows: for D-I, the use of a central command to coordinate security responses; for D-II, restricting critical areas; and for D-III, having a written risk management plan.

Across all divisions, the following strategies seem to work: having a risk management plan, using a central command to coordinate security responses, and having a minimum of one security personnel for every 250 spectators. Other effective strategies are live security patrols, use of visual inspection of spectators upon entry, having an ambulance and/or paramedic onsite, and having an athletic trainer and/or medical doctor onsite.

Nonetheless, what is most compelling are the explanations of why athletic facility managers believe a strategy to work. For instance, one facility manager indicated that having a risk management plan is effective because “we have had an ‘active shooter’ near campus and our [lockdown] procedures ensured anyone in our facilities were safe until local law enforcement gave an all clear.”

Another facility manager supports having a central command to coordinate security responses because “we have had fire alarms pulled in the arena, and by having a central command we were able to check the area where the alarm was pulled quickly and not have to evacuate the building for a fraudulent alarm.” Yet another indicated having a central command allows others to confidentially report the details of a weapon threat, so that individuals are “apprehended before any incident and without mass public knowledge.”

Several comments indicated that live security patrols catch people trying to sneak into games, break into patron vehicles, and use alcohol. Additionally, medical personnel onsite help to improve the response time and reduce severity of injuries; the benefit of this measure was described by one respondent: “We had a full cardiac arrest … and the patient was breathing when he left.” Another respondent indicated medical personnel are “excellent in reducing pain, injury, [and] suffering that could lead to legal action.” Other athletic facility managers presumed risk management strategies to be effective, suggesting that a lack of incidents indicate the strategies are working to deter risk.

Respondents made other significant comments about what strategies work:

Jersey barriers within 100-feet of facility perimeter: “Very effective—keeps large groups from causing potential harm to self and others.”

Jersey barriers within 100-feet of facility perimeter: “Very effective—keeps large groups from causing potential harm to self and others.”- Updating background checks: “[It’s] effective in that on one occasion, we found out that an individual had an arrest that would otherwise have gone unmentioned to us, causing that individual to not be renewed.”

- Issuing zone passes to limit/restrict access: “Having a media badge has been very effective. It also gives the event staff authority to ask someone without those permissions to leave. It has reduced the incidents of people not being where they belong greatly. It educates them as to where they are allowed to be or not to be. It educates our event staff to pay attention to where people are and [to] consider if they are allowed to be there or not.”

- Surveillance cameras to monitor entire facility: Reports have indicated effectiveness in locating missing children, identifying fights and intoxicated individuals, and solving robberies.

Risk Management Strategies Reported to Not Work

Multiple strategies seem to not work, however (D-I, six strategies; D-II, nine strategies; and D-III, five strategies). But the divisions agree on only five of the strategies that do not work: issuing photo identification passes to all employees (D-II and D-III); issuing personal identification cards, badges, or passes for all media personnel (D-I, D-II, and D-III); use of visual inspection of spectators upon entry (D-I and D-II); electronic scanning of all tickets (D-I and D-II); and signage detailing security practices and restricted items (D-I and D-II).

Yet the one strategy whose effectiveness (or lack thereof) was not addressed by any respondent is that of restricting backpacks and other large bags carried in by spectators. This silence is especially surprising, since a majority of D-I respondents use this strategy.

Respondents made the following significant comments about what strategies do not work:

- Issuing personal identification cards, badges, or passes for all media personnel: “Some credentialed pass holders ‘talk their way into events.’”

- Minimum of 1 security personnel for every 250 spectators: “We had a student run on our basketball court during a game” and “occasional theft or vandalism … nothing will work 100% of the time.”

- Electronic scanning of all tickets: “If forged tickets get scanned first, the real ticket holder can be rejected.”

- Signage detailing security practices and restricted items: “Participants don’t always read.”

Since several respondents reported that some risk management strategies do not work, this begs the question of why they are using a strategy that they may deem ineffective. Despite many comments indicating that certain risk management strategies do not work all of the time, if those strategies reduce risk, they can still be considered effective.

Applicability to Facility Managers and Future Research

This study examines NCAA athletic facility managers’ perception of effectiveness of their risk management strategies. In a survey, 113 athletic facility managers across all three NCAA divisions reported their use of 34 risk management strategies as recommended by Pantera et al. (2003). However, inconsistent with Pantera et al., the only risk management strategy used by all respondents is having “an athletic trainer or medical doctor onsite.” For those strategies that are used, many are perceived as effective, such as “having a central command to coordinate security responses,” while others may occasionally lack perceived effectiveness, such as “signage detailing security practices and restricted items.”

Athletic facility managers can use the results of this study to compare perceptions of effective risk management strategies used at other institutions. These findings may also be relevant to managing other campus facilities, particularly those that accommodate large groups and support large events. This may, in turn, help prevent legal liability, reduce costs of litigation, avoid reputational harm, and make communities safer.

Future studies should examine if athletic facility managers similarly define risk management and how and why they select their risk management strategies. Additionally, the perceptions of athletic facility managers could be compared to those of their other campus partners (fire, police, environmental and safety, campus legal and risk management teams, etc.), as they might have similar or different perceptions of the effectiveness of risk management strategies.

Table 1. Athletic facility managers perception of effectiveness or lack of effectiveness of 34 risk management strategies to reduce risk*

Bibliography

Alfano, S. (2005, October 1). Explosion kills one near stadium. The Associated Press. Retrieved from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/explosion-kills-one-near-stadium/

Hall, S., Marciani, L., Cooper, W. E. & Rolen, R. (2007a). Introducing a risk assessment model for sport venues. The Sport Journal 10(2). Retrieved from https://thesportjournal.org/article/introducing-a-risk-assessment-model-for-sport-venues/

Hall, S., Marciani, L., Cooper, W. E. & Rolen, R. (2007b). Securing collegiate sport stadiums in the 21st century: Think security, enhance safety. Homeland Security Institute: Journal of Homeland Security.

Inge, V. E. (2012, June 15). Risk management for athlete safety and to protect facilities from spectator lawsuits. Sports Litigation Alert, 9(11), 6. Retrieved from https://sportslitigationalert.com/risk-management-for-athlete-safety-and-to-protect-facilities-from-spectator-lawsuits-2/

McCann, M. A. (2006). Social psychology, calamities, and sports law. Willamette Law Review, 42, 585-637.

Pantera III, M. J., Accorsi, R., Winter, C., Gobeille, R., Griveas, S. Queen, D., Insalaco, J. & Domanoski, B. (2003). Best practices for game day security at athletic & sport. The Sport Journal, 6(4). Retrieved from https://thesportjournal.org/article/best-practices-for-game-day-security-at-athletic-sport/

Sugiura, K. (2011, March 9). Recalling the tornado of 2008 SEC tournament. Atlantic Journal-Constitution. Retrieved from https://www.ajc.com/sports/college/recalling-the-tornado-2008-sec-tournament/AYY5lYigBSdqdzWeI7jeFM/

Whitley, J. D., Koenig, G. A. & Roberts, S. E. (2007). Homeland security, law, and policy through the lens of critical infrastructure and key asset protection. Jurimetrics, 47(3), 259–280.

Angela Hayslett is a lecturer at James Madison University, Harrisonburg, VA, and can be reached at [email protected]. Emeka Anaza is an associate professor at JMU and can be reached at [email protected]. This article summarizes the authors’ research project CFaR042-20, conducted under the auspices of APPA’s Center for Facilities Research. Read the complete research report here.