COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) has forced many higher education institutions to adjust operations across campus. The impacts of SARS-CoV-2 are seen everywhere on campus and felt within every department. When the pandemic began, many facilities management organizations (FMOs) pivoted to ensure safe and healthy facilities while maintaining continuity of service. As FMOs began to prepare for the fall semester, they began collaborating with campus stakeholders to assess, plan, and implement a design for the upcoming semester. In many cases, these circumstances led to an unprecedented planning exercise—one with no playbook to reference.

Figure 1: An illustration of the SARS-CoV-2 virus from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In the absence of a standard manual to address the challenges related to SARS-CoV-2, many organizations looked to the familiar hazard-mitigation framework for guidance.¹ This approach led many campuses to conduct risk assessments for each proposed in-person and on-campus activity. The risk-assessment process facilitates the identification and prioritization of all hazards and risks.

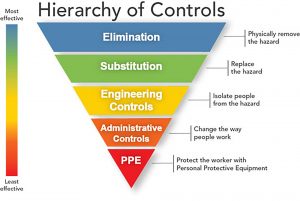

The evaluation of potential controls is a critical component of the risk assessment. The hierarchy of controls is depicted as an upside-down triangle. Control methods at the top of the triangle are more effective, whereas those at the bottom are less effective. The following sections of this article outline some common controls deployed by many educational institutions to mitigate SARS-CoV-2.

Figure 2: The hierarchy of controls as illustrated by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Elimination and Substitution Controls

Elimination controls are the most effective and preferred of all possible controls. These controls either physically remove the hazard or substitute the hazardous conditions with less hazardous ones. A classic example of an elimination control is turning off the power and ensuring it is locked out at the electrical panel before starting any electrical work. Substitution controls involve replacing the hazard; one example of a substitution includes replacing a volatile organic compound (VOC)-laden solvent-based paint with a no-/low-VOC water-based paint.

Remote Operations

Remote work allows the institution to eliminate an individual’s opportunity to contract SARS-CoV-2 while on campus. This control option is the most effective. However, many institutions find that it is not feasible for FMOs and some other departments to transition to a 100-percent remote-work solution. Campus buildings will continue to need the support of FMOs for various maintenance and infrastructure operations. Similarly, some academic activities are challenging to accomplish via remote options and may require an in-person presence (e.g., some research activities or class lab sessions).

Digital Tools

Digital tools may provide a reasonable substitute for traditionally in-person tasks. Meetings shift easily to virtual platforms, allowing staff to maintain continuity of operations. Many digital tools allow secure sharing of screens or remote desktop access. Personnel should investigate opportunities to utilize digital tools to aid and enhance their duties and virtual learning. However, it is important to note that digital tools are vulnerable to internet-bandwidth and power outages. For example, on August 20, 2020, Zoom users experienced a four-hour outage of all services; the outage correlated with the first day of school for many institutions.

Premade Kits

Departments may elect to substitute in-person experiments and modules by assembling and distributing premade kits. These kits contain the materials needed for students to accomplish nonhazardous course components at home coupled with virtual instruction. The kits can be distributed via a one-time drive-through pickup or sent via the postal service. This control measure helps maintain a low campus population density, thus reducing the overall risk of infection. In the case of FMOs, this option may allow some labs to remain offline, allowing custodial staff to shift their sanitization efforts to more public spaces and heavily trafficked areas.

Class-Size Reduction

Physically present class population size can be reduced to minimize both the frequency and intensity of contact with other individuals. Alterations can be made to the delivery of various curricula so that only one-third of the participants are present in person, while two-thirds attend class and observe remotely through digital tools. This method allows for the rotation of students every two weeks, so they can physically come into their class or lab to gain the necessary hands-on experience.

Furthermore, this control allows for students with validated medical concerns and student disability service waivers to participate remotely in lab sessions as part of a larger cohort. This method creates opportunities for peer-to-peer learning, as the in-person participants will pass along their knowledge and experience to their group.

Space-Configuration Changes

Personnel may elect to substitute a different type of space to hold necessary face-to-face interactions. A common example of this measure is moving a meeting to a larger physical space. Sometimes effective implementation may require space reconfiguration to accommodate the meeting, for example, transitioning a large building atrium into a space featuring physically distanced study carrels. Such changes may require furniture moving, cleaning schedule changes, and adding extra power. Changing spaces for regularly scheduled courses includes working with the registrar and department(s) on moving into a different space.

Individuals may opt to investigate holding a meeting in an outdoor space, which requires scheduling and planning of the intended space to ensure it can properly support the meeting. FMOs may need to provide temporary seating and wastebaskets. FMOs should alternate the landscaping schedule to minimize noise disruptions. Staff must also plan for appropriate configuration of the space to ensure all participants can comfortably and safely maintain physical distancing. As a precaution, FMOs should encourage those who plan to meet outside to have a dedicated alternative space ready in the event that weather poses an inconvenience (i.e., too hot or cold) or turns severe.

Engineering Controls

Engineering controls isolate the hazard from the population and include process controls, enclosure/isolation, and ventilation. Process controls are methods of altering the task to reduce risk. Enclosure and isolation are techniques used to keep the hazard out or away from the individual. Ventilation controls remove dangerous gases from spaces (i.e., laboratory fume hoods). The process control of using water to minimize dust when drilling or sawing concrete is an example of an engineering control.

Physical Distancing Modifications

This technique complements several of the previously mentioned measures, specifically class-size reductions and space-configuration changes. Once the designated spaces for in-person activities are identified, some modifications to accommodate physical distancing may be required. Classrooms and meeting rooms require an assessment to determine the safest occupancy and best space layout. Whenever possible, the assessments should occur in-person, as floor plans may not offer an accurate depiction of the space. FMOs may need to remove furniture from the room or cordon it off as space allows. In stationary seating areas, e.g., lecture halls or theaters, seats may need a physical marking or obstacle installed to discourage use.

Figure 3: An example of a physical distancing floor marker.

Points of service and queuing areas may require visible markers installed according to the current physical distancing guidelines. When planning for potential long lines, FMOs should work with the stakeholders to determine the best configuration of lines and should take care not to encumber fire life safety stations, egresses, stairwells, elevators, hallways, and amenities. Finally, FMOs may wish to evaluate and provide physical distancing guidance relative to elevators and pedestrian traffic directions.

Personal Item Storage

An example of an isolation measure is providing ad hoc spaces for personal items. This measure encourages individuals to store items that are not regularly cleaned within a certain area for the duration of the meeting. This control allows for bookbags, winter coats, lunch bags, and other items to remain separate from the rest of the population in that space, ensuring that each person has limited contact with/exposure to others’ personal items.

HVAC Systems

ASHRAE has issued the following guidance on addressing HVAC systems and mitigation: Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 through the air is sufficiently likely that airborne exposure to the virus should be controlled. Changes to building operations, including the operation of heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning systems, can reduce airborne exposures.

Ventilation and filtration provided by heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning systems can reduce the airborne concentration of SARS-CoV-2 and thus the risk of transmission through the air. Unconditioned spaces can cause thermal stress to people that may be directly life threatening and that may also lower resistance to infection. In general, disabling of heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning systems is not a recommended measure to reduce the transmission of the virus.²

Administrative Controls

Administrative controls change the way we perform our work. This class of controls often consists of new or modified policies, training, guidelines, hygiene practices, and scheduling. These controls limit exposure to the hazard and are implemented when the exposure cannot be 100 percent mitigated by the above controls.

Physical Distancing

Personnel and students should maintain physical distancing (i.e., 6 ft.) whenever possible. In the event physical distancing is not possible, personnel should ensure that proper personal protective equipment (PPE) is worn. Institutions should issue consistent guidelines to define physical distancing and provide guidelines to maintain physical distance.

Schedule Compression

Schedule compression provides opportunities to limit a population’s frequency of exposure. In the context of FMOs, this could include working a 10-hour day, working every other day, or taking turns working in the morning and afternoon. From an academic perspective, when classes/labs are small enough, schedule compression allows for completion of all lab activities during a two- or three-week portion of the semester. This allows the population to come to campus for one or two weeks to complete the in-person training before resuming remote options.

Symptom Surveillance

Many institutions have implemented symptom surveillance of those living, working, and teaching on campus. Departments or individuals may wish to communicate prior to scheduling an in-person meeting for confirmation that neither party is experiencing any symptoms of illness. This method helps to reduce potential contact/exposure with pathogens. Additionally, it serves to mitigate any anxiety that may be associated with meeting face-to-face.

Sanitization

Sanitization and housekeeping efforts on campus have increased. The increase in these operations provides opportunities to demonstrate effective sanitization practices and encourage proper personal hygiene. FMOs could locate disinfectant stations (i.e., a spray bottle and wipes) in high-utilization classrooms and meeting rooms. This encourages the population to wipe down surfaces before and after they use them. Additionally, proper hand hygiene should be encouraged through means such as providing additional hand sanitizer dispensers and disseminating communications related to proper handwashing techniques.

Syllabus Communication

Personnel should provide a SARS-CoV-2 expectations addendum within their syllabi. This could include an overview of the controls implemented and an outline of unique procedures developed for a particular course in response to SARS-CoV-2. Additionally, the addendum should provide information about what students should do if they fall ill.

Temperature Checks

Individual departments may elect to establish a daily temperature check for each person participating in face-to-face operations and require them to log their temperatures prior to the start of the class/meeting. If an individual registers a fever, they should remove themselves from the group, begin self-quarantine, and continue to monitor symptoms. If the condition worsens, individuals should seek immediate medical care. This control serves to eliminate the exposure of the entire group to a potentially sick individual.

Assignment of Spaces/Assets

Personnel may consider the assignment of seats, lab benches, or computer stations to ensure that a student is in the same place for each meeting for the duration of the semester. Implementing this procedure would greatly aid in the event that contact tracing is needed. Personnel may consider the assignment of assets or equipment to a specific individual, which will ensure that a piece of equipment that cannot be thoroughly sanitized is only used by that person for the duration of the meeting (i.e., no transmission from person to person).

Conclusion

The above summary provides only a brief overview of some of the more common controls available to FMOs to help mitigate risks associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Some specific situations may require a set of controls that are not discussed here. Effective controls are both well documented and easily modified as needed. Furthermore, it is important to remember that all controls will require some level of monitoring and verification to ensure they are working as designed.

REFERENCES

1. https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/2018-12/fy10_sh-20854-10_hazard_id_facilitatorguide.pdf

2. https://www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/resources

Ryan Kmetz is assistant director of sustainability at the University of Maryland Baltimore County; he can be reached at [email protected]. Kmetz is a past recipient of APPA’s Rex Dillow Award for Outstanding Article in Facilities Manager.