Construction is the third and, arguably, the most important of the three phases of project delivery (Project Planning, Design, and Construction). This is where oversights, shortcomings, or errors cost big money. Construction is dangerous, both to workers and to the public. Changes during construction are typically expensive and, usually, substantially more expensive than a design change. Construction can also be disruptive to an educational campus and potentially hazardous to both construction workers and campus residents.

In the United States, there are three common methods of procuring a contractor for construction of public projects:

- Design-Bid-Build (D-B-B) where a project is completely designed, let for competitive bidding, and the low bidder is awarded the construction contract (assuming that the low bidder is qualified and capable of performing).

- Design-Build (D-B) where a contract is left to a team consisting of a qualified designer and a contractor who will work in tandem to design and construct a facility.

- Construction Manager at Risk (CMAR) where a design is completed only to the point where a qualified contractor can provide a Guaranteed Maximum Price to deliver a completed building.

While the choice of methods may be governed by local statute and practice of by government procurement agents, these three methods are in broad use across the United States. There are advantages and disadvantages of each method.

D-B-B: This is the traditional method of public construction procurement that has been institutionalized for decades. It accounts for over half of the construction contracts in the United States. Many procurement officers feel that this method will guarantee the lowest price for the work because contractors must compete based on price to “win the job.” Using this method, the owner has almost complete control over what is to be constructed. The owner, for example, can specify the brand of doorknobs to be used and the color and even the brand of wall paint to be used. There are many disadvantages to D-B-B. Because the contractor had to low bid the job to be awarded the contract, there is often an adversarial relationship between contractor and owner because the contractor is looking for ways to add to his construction contract by change orders. In addition, this method takes substantially more time than other methods because the design must be 100% complete before construction begins, and the typical government procurement processes to advertise and award has prescribed times.

D-B: This process came about in the early 1990s because of the increasing construction claims that were raising the cost of construction of public projects. It was felt by some agencies that by simply developing a performance specification, selecting a D-B team based on qualifications and allowing the contractor to use its ingenuity, skills, and experience to construct a facility that met the specification, both time and money would be saved. Moreover, the adversarial relationship of D-B-B could be avoided. In practice, this process saved time but not much money because the D-B team then assumed the risks inherent in construction. Moreover, the owner had very little control over the final product or whether it met the performance specification.

CMAR: This method attempts to marry the best characteristics of D-B-B and D-B by completing a design only to the extent that a qualified contractor can provide a guaranteed maximum price for the finished product. The owner/designer specifies those features of most importance including the type, size, location, and specifications of the facility. About 1/3 through the design process, when most of the features are determined, the owner will solicit statements of interest and qualifications from qualified contractors. Then, the owner will select the contractor most qualified and will work with the firm to complete enough of the design to provide a firm fixed price. Using this method, the owner gives up some control to the contractor but works with the contractor as a team instead of as an adversary or a bystander in the project delivery process.

The key players in construction—their roles and responsibilities

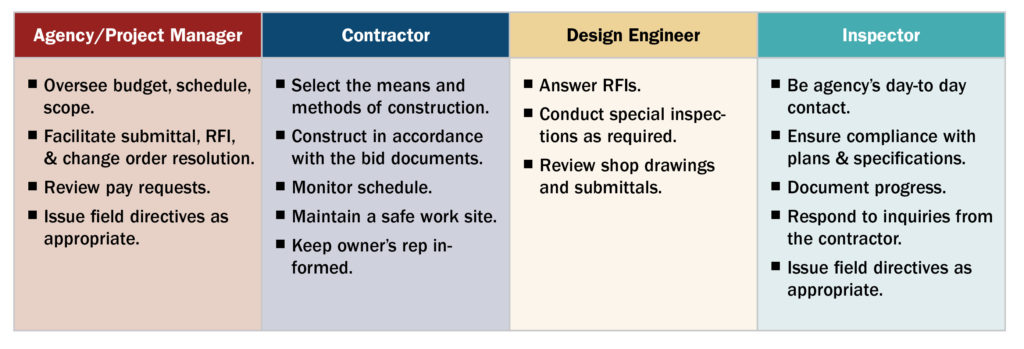

There are several players in the project delivery process as it moves from design to construction. Each has a part to play, and each has specific responsibilities. In a well-run project, all members, each representing a specific agency’s interests, work as a team towards successful project delivery. Because roles can overlap, it is not uncommon for one player to usurp the role of another; when this happens, conflicts can occur. Here are the key players and the roles that they play.

There are several players in the project delivery process as it moves from design to construction. Each has a part to play, and each has specific responsibilities. In a well-run project, all members, each representing a specific agency’s interests, work as a team towards successful project delivery. Because roles can overlap, it is not uncommon for one player to usurp the role of another; when this happens, conflicts can occur. Here are the key players and the roles that they play.

- Contractor: The contractor is responsible for the construction of the project and for its successful delivery. In this role, the contractor is solely responsible for building the project including selecting the means and methods of construction; ensuring job site safety and security; managing the subcontractors; constructing the project in accordance with the plans, specifications, and current codes; maintaining the schedule; and keeping the owners representative informed of progress and any issues that might impact construction progress.

- Designer: While the bulk of the designer’s work has been completed during the pre-construction phases of the project, the designer’s role should continue through project delivery to assure that the design intent is met and to answer design questions that inevitably occur during construction. Shop drawing review, evaluation of substitute materials, and responding to Requests for Information (RFIs) are all the purview of the designer who is the only one qualified to interpret design intent.

- Owner’s Representative: The Owner’s Representative is a staff person or third-party consultant engaged to represent the interests of the owner as the project is under construction. The owner’s representative should participate in progress meetings, evaluate and recommend (or reject) contractor requests for payment, evaluate and recommend requests for material substitution, coordinate the activities of the contractor with the institution’s operations, and more generally, act as a liaison between contractor, designer, and owner.

- Inspector: Depending on the size and complexity of a project, an owner may wish to employ an inspector to provide day-to-day assurance that the plans and specifications are being met and that the facility is being constructed properly. In addition, the inspector will document progress by regular reporting and documentation, including photographic documentation, of progress. In addition to the owner’s inspector, building inspectors from the local jurisdiction can be expected to periodically oversee aspects of the construction for compliance with applicable codes and building standards.

While each player has an important role, it is essential that each understands the extent and limit of their authority. For example, if the owner has not designated where construction personnel are allowed to park personal vehicles in the special provisions, and partway through construction the owner’s representative places restrictions on the number of parking places or where on the campus workers can park, this may result in a dispute and a contractor claim may result because the “means and methods of construction” are being interfered with.

Measuring and documenting construction progress

As construction proceeds, it is essential that progress be measured against a projected schedule and budget and that progress be documented. There are several important purposes for regular project reporting using a simple but standard format.

As construction proceeds, it is essential that progress be measured against a projected schedule and budget and that progress be documented. There are several important purposes for regular project reporting using a simple but standard format.

- Inform key stakeholders of the status of the project and to forecast anticipated progress.

- Alert key stakeholders of potential issues that may affect project delivery, cost, schedule, or scope.

- Provide a contemporaneous report of the status of the project at any given time.

- Request information or other input from stakeholders.

- Document scope changes, risk factors, and project conditions.

- Alert stakeholders and others of potential project changes.

This report should not be burdensome, nor should it be extensively detailed. Basically, it should simply answer the following questions:

- Where are we on the project?

- Where are we going next?

- What is the status of the schedule and budget?

- Have there been any scope changes?

- What, if anything, do we need from the owner/designer/key stakeholder to keep the project on track?

- What other issues or concerns are there that can potentially impact project delivery?

- What is the status of the identified risks or newly identified risks?

The answer to these questions can be easily formatted into a simple, one page, progress report that is easy to prepare, easy to disseminate, and easy to read; the text of the report can be augmented with photographic documentation as appropriate. This report should be submitted by the contractor with its monthly invoice. Insist on a monthly invoice, this requirement should be in the standard contract documents (contract boilerplate).

This practice, done consistently has many benefits. Regular reporting:

- Can head off stakeholder questions that may require time-consuming research or data-gathering.

- Allows you to control the agenda and can focus on what is really important.

- Provides a contemporaneous record of what happened on the project.

- Highlight project needs, stakeholder input, and project scope changes.

- Is the ultimate “client touch” whereby your clients/stakeholders/customers will be kept informed and you, as a project manager, will be recognized as professionals.

Avoiding construction claims

The first step in avoiding construction claims and contract disputes is to understand the world that the contractor lives and works in. Construction is expensive—costly materials are subject to theft and deterioration if left in the weather. Labor and equipment rental are expensive and can often be difficult to find. And retaining qualified labor can be difficult. Thus, in the construction world, time is money.

The first step in avoiding construction claims and contract disputes is to understand the world that the contractor lives and works in. Construction is expensive—costly materials are subject to theft and deterioration if left in the weather. Labor and equipment rental are expensive and can often be difficult to find. And retaining qualified labor can be difficult. Thus, in the construction world, time is money.

The leading cause of construction claims is delay. Any time that a contractor is delayed, regardless of the cause, will cost money and erode the profit margin on the contract.

Some delays are inevitable—weather, for example, or the inability of a key supplier to deliver on time because of a labor dispute. These are out of the control of the owner or designer as well as the contractor. But the contractor will take the loss.

There are matters that the owner and designer can control, and if not attended to, can cause delays and potentially claims or requests for reimbursement. Contractor RFIs, shop drawing reviews, and contractor inquiries must all be logged, tracked, and followed up on to prevent contractor delay.

Some best practices are listed below.

- Develop and maintain a collegial working relationship between the owner, designer, and contractor. A well-established best practice in the industry is a process called “Partnering.” While it is beyond the scope of this article to delve into a detailed discussion of the practice, suffice it to say that a partnering session culminating in a partnering agreement—that includes a process to resolve the inevitable issues that can occur on construction projects—can serve to develop a strong relationship between the parties.

- Insist on consistent and regular progress reporting as described earlier in this article.

- Ensure consistent and continuous involvement by the same knowledgeable owner’s representative. If any of the key players, (owners representative, design project manager, inspector, contractor’s superintendent) experience inconsistencies in direction, potential confusion and delay while matters sort out can result.

- Consistently use logs and registers to track contractor communications such as RFIs, shop drawings, and other contractor communications. These logs should be reviewed at regular construction meetings. Ask, at every construction meeting, “Do we owe you any information?”

- Pay promptly. A best practice is to ensure payment of an approved invoice within 30 days. And ask at the construction meetings: “Are you being paid on time?”

Project acceptance and contract closeout

Project acceptance and contract closeout

There is a saying in the construction world that, “The project is not over until you are sick of it.”

Unfortunately, there is more truth than fiction in this quote. Typically, as a project nears completion, three things happen:

- The team (including the contractor and the designer) begin to demobilize and move on to another project.

- Everyone is out of budget and the schedule is against the wall.

- Cleaning up the loose ends is not fun.

Concurrently the owner wants/needs to use the new facility.

It is this phase of the project when strong leadership is needed. As a best practice, the owner’s representative should hold a “red zone” meeting with all concerned including the contractor and the design team and simply ask the question, “What needs to be done, so that we can finish construction and close out the contract?” From that meeting, develop a to-do list, assign responsibilities, and start to work on the remaining issues. Develop a process for regular follow-up and closeout of individual tasks.

In the project closeout process, there are three levels of “closeout.”

- Component Closeout: A component of the project is complete and has been accepted. The subcontractor or supplier can be paid in full, and the contract closed out. A roof, for example, can be inspected and accepted, and the roofing component can then be closed out.

- Substantial Completion: Sometimes known as “beneficial occupancy” is when a project can be safely and properly used for its intended purpose but there are still “punch list” items that need correction. Caution should be exercised when occupying a facility before final completion, inevitably some damage can occur as the building is occupied and then the discussion becomes, “Is this a punch list item, or damage caused by the occupant?” A thorough punch list, documented with photographs, can preclude this.

- Final Completion: As the title suggests, the project is complete, all contract provisions have been met; documentation, manuals, and staff training are complete; and the project records are compiled and prepared for archive. As-Built drawings have been assembled and reviewed for accuracy and are maintained in the project records. At this point, the contractor retention can be released and the contract can be closed.

Michael S. Ellegood, P.E., is a practicing civil engineer, a former senior executive of major international engineering firms, and a former large county public works director. He serves on the Arizona State School Facilities Oversight Board, the state agency charged with overseeing all public-school construction in Arizona. An experienced project manager, he has published articles and conducted training on project management. He can be reached at [email protected].