There is a minor departure this edition from the usual two book column to just one. It allows me to discuss a topic of concern to all professionals, whether licensed or not: Ethics.

Engineers know many things about how the world works and that danger may be around the corner if one ignores technology. Therefore, they must behave ethically and avoid a focus on profit over safety. I hope you enjoy the column and will consider the book as a result.

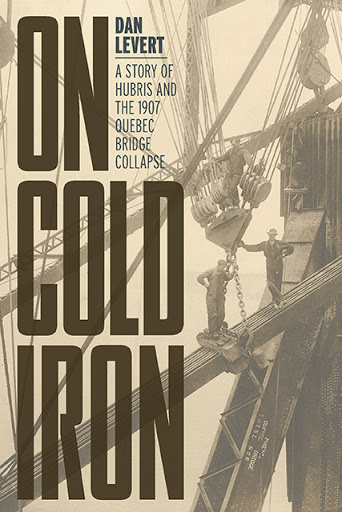

ON COLD IRON: A STORY OF HUBRIS AND THE 1907 QUEBEC BRIDGE COLLAPSE

Levert, Dan, FriesenPress, 2020, 276 pages, $10 e-book, $14 softcover, $20 hardcover

Over twenty years ago, this column reviewed a book by William Middleton about the Quebec Bridge. Looking at the work of another author can increase one’s perspective on the subject or reinforce some ideas that may have been under consideration. That’s the case with this book. On Cold Iron by Dan Levert is a clearly written account of the behavior of individuals involved with the construction of the longest cantilever bridges in the world, a record not surpassed in over 100 years.

Over twenty years ago, this column reviewed a book by William Middleton about the Quebec Bridge. Looking at the work of another author can increase one’s perspective on the subject or reinforce some ideas that may have been under consideration. That’s the case with this book. On Cold Iron by Dan Levert is a clearly written account of the behavior of individuals involved with the construction of the longest cantilever bridges in the world, a record not surpassed in over 100 years.

Those who read Middleton’s book, or who are familiar with the Quebec Bridge, know the tremendous loss of life during the construction of the first version of the bridge, and understand how it affected people in the Quebec City area and the engineering profession. Levert is not shy about the topic and introduces the book with discussion about the Ritual of the Calling of the Engineer. The Ritual, only in Canada, was created by several Canadian engineering academics with the assistance of Rudyard Kipling. The intent of the Ritual is to impose on engineers the same ethos of responsibility to protect the lives of the public. It was intended to be the engineering equivalent of physicians’ Hippocratic oath.

It’s one thing to hear about a ritual and the goals of its developers to impress upon engineers about their obligations outside of legislative strictures. It’s another thing to provide sufficient background about the importance of the goals. That’s where the succeeding chapters of On Cold Iron provide the rationale. The story of the Quebec Bridge is one of high-minded goals to serve the citizens of Quebec and to achieve something remarkable. The remarkable thing was to construct a bridge, one of the many things for which great engineers are recognized. Major bridges prior to the Quebec Bridge included the Eads Bridge in St. Louis, and the Brooklyn Bridge in New York. These bridges saw loss of life due to various risks that engineers were still learning about. But the loss of life at the Quebec Bridge far exceeded the combined loss of life of the other two great bridges.

At the turn of the century, deaths due to accidents at large construction projects were not normal but also not unheard of. Engineers and builders have learned a lot since then about how to keep workers safe. However, much of what caused the loss of life at the Quebec Bridge, as is described in non-technical terms in On Cold Iron, was known, understood, and preventable. The most famous engineer of the time, Theodore Cooper, was hired to oversee the design of the bridge. He had designed and constructed numerous bridges previously and had developed a system for rating bridge capacity that is still used today. He didn’t visit the site during construction and relied on reports from supposedly knowledgeable individuals on site. However, over-confidence and some poor assumptions were ignored, and on-site observations were dismissed.

The hubris exhibited by several people involved in the design and construction of the bridge is on full display. The investigation after the partially built bridge collapse identified several reasons for the failure and lost opportunities to prevent the collapse. However, virtually everyone involved was exonerated. Recommendations were made to prevent a similar disaster after the bridge wreckage was removed, and the new bridge constructed, had changes to the design approval process. More importantly, the investigation identified the need for greater responsibility to protect the safety, health, and welfare of the public (including workers on site).

Since the Quebec Bridge, and the creation of the Ritual of the Calling of the Engineer, professional engineering organizations have developed codes of ethics that place paramount the protection of the safety, health, and welfare of the public. In the United States, a corresponding ceremony, the Order of the Engineer, emphasizes similar obligations to Canada’s Ritual. It’s designed to emphasize the importance of a public duty for good. Regardless of one’s subsequent employment in engineering, the Order of the Engineer builds on the ethical responsibilities of engineers described in On Cold Iron. If you ever wonder why engineering organizations and licensure rules place an emphasis on ethics, be sure to read On Cold Iron to get your answers.

Ted Weidner is professor of engineering practice at Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, and consults on facilities management issues, primarily for educational organizations. He can be reached at [email protected]. If you would like to write a book review, please contact Ted directly.

Bookshelf

Book reviews on current publications relevant to the profession, trends, and working environment of facilities and educational managers and professionals. To contribute a book review, contact Ted Weidner, field editor of this column.

See all Bookshelves.