People change faster than the facilities that support them. Closing this gap requires a continuous process of planning, designing, operating, and assessing facilities. Doing this successfully better aligns classrooms, labs, offices, study spaces, dining, event spaces, and residence halls with the needs and perceptions of the people who use them.

Changing demographics and expectations

According to various sources, in the United States:

• 57% of students prefer classes that are hybrid, blended, or online.

• Only 65% of students feel a sense of belonging.

• Interdisciplinary science is fast becoming the norm, with 49% of papers in the social sciences and 35% in the physical sciences crossing disciplines as of 2015.

• 81% of students expect experiential learning on real-world projects.

• Students overall are more diverse than ever before in many ways: 19% have a disability, 20% identify as LGBTQ+, 37% are adult learners over age 25, and 42% are students of color.

These can all change the way people choose to learn, live, and work.

Keeping up with the pace of change

Not surprisingly, many higher education leaders struggle to keep up with all this change. At a roundtable discussion one of the authors of this article facilitated, a finance and budget director noted, “You can’t plan for the speed at which things are happening.” An AVP of student life observed, “You have to make the best decision you can with the information you have at the time. We have to be nimble.” An AVP of facilities said, “The era of continuous expansion is over.”

Further, institutions move from strategic plans to campus plans to capital campaigns to renovations and expansions that can span a decade or more. This makes it challenging to quickly respond by aligning spaces, programs, services, and technology.

Several other factors must also be considered in the struggle to keep up. For example, as financial models change, capital projects depend more on donors who may develop ideas that don’t always align directly with the institution’s goals. Similarly, as colleges and universities partner with companies and other community groups for student class projects, research initiatives, or other programs, these partners must also be involved in planning and operations.

Sometimes institutions create functional organizational structures that can widen gaps further. For example, at many colleges and universities, those responsible for leading academic programs, like provosts, deans, and department heads, have no contact with those planning, building, and operating the facilities that support those programs. Misalignment of goals is not uncommon.

But it’s not all doom and gloom!

How institutions are responding

The Society for College and University Planning’s annual Campus Facilities Index found that institutions are working hard to keep pace. The 2023 report found that in the next year:

- 77% of colleges and universities planned to create more active learning classrooms.

- 77% of colleges and universities planned to create flexible/unassigned workspace for staff.

- 48% of colleges and universities planned to renovate or expand facilities for affinity/cultural groups.

An annual national student experience survey by Brightspot, where one of the authors is a partner, found relatively high percentages of student satisfaction with campus facilities like libraries (76%), athletics and rec spaces (75%), and labs (71%), but less so with student health centers (63%), housing (63%), and dining facilities (60%).

Students are also voting with their feet, with the use of library, dining, and fitness facilities increasing, according to another Brightspot study.

Significant changes like online/hybrid learning and remote/hybrid work can have substantial benefits for students and institutions alike. They make campuses more sustainable socially by increasing access, economically by reducing facilities’ needs and costs, and environmentally by reducing the carbon and physical footprint.

Significant changes like online/hybrid learning and remote/hybrid work can have substantial benefits for students and institutions alike. They make campuses more sustainable socially by increasing access, economically by reducing facilities’ needs and costs, and environmentally by reducing the carbon and physical footprint.

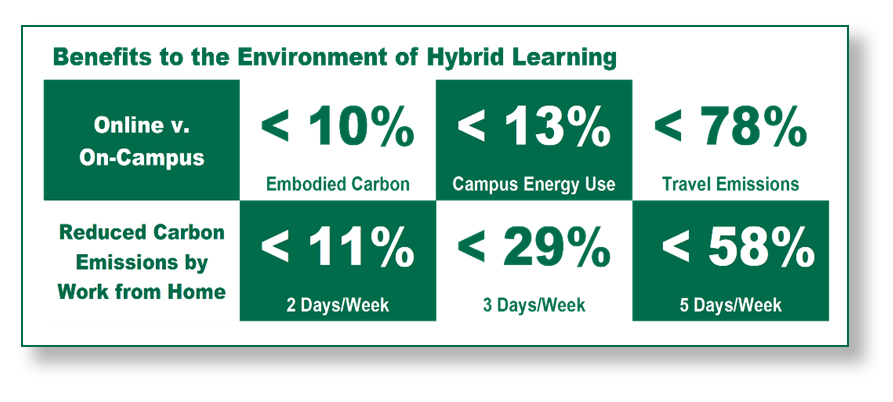

Still another Brightspot study found that the median carbon footprint of a typical online MBA student is less than half that of an on-campus MBA student, at 2,200 versus 4,700 kgCO2e (kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent)/student/year. About 10% of the savings comes from avoiding the embodied carbon of additional buildings, 13% savings come from campus and home energy use, and 78% from reduced travel emissions.

Similarly, a recent study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that working from home two, four, and five days per week reduces carbon emissions by 11%, 29%, and 58%, respectively.

Aligning academics, facilities, and technology

Given these changes, how can academic and facilities leaders best ensure that spaces keep pace with what people need? Steps to addressing change can include:

- Creating integrator roles: Most successful infrastructure projects have someone on the client team charged with integrating academic needs and the facilities and technology to meet them. This person might be a director of space planning in the provost’s office or the vice president of research—someone who is well-versed in how instruction and research are changing the space and technology needed.

- Designing institutional and project governance: Another approach is to create structures that bring together academics and infrastructure. These might include a campus committee on space planning and management that aligns space “supply” with academic program “demand.” It might also involve standardizing the selection process for planning and design firms and the project governance structure, such as the stakeholders who will provide input and feedback, the working committee that will make recommendations, and the steering committee that will make decisions.

- Developing collaborative deliverables: The right roles and structure can also facilitate creating key deliverables that start the alignment process early. These might include a standard project justification or business case template, which a group would fill out to describe its needs for a renovation, expansion, relocation, or other facilities change. For projects that are approved, a standard project charter that distills the background, team, goals, and risks can also help with alignment. Education about using these tools, notably for academic leaders, is vital to their success and must be included early in the process.

- Creating a culture of foresight: To ensure projects are not just short-term and reactive, build a culture of thinking and planning ahead. Regularly reviewing trends, assessing the performance of and lessons learned from past projects, and strategically forecasting future needs and tactics can help. For example, eliminating distributed or redundant spaces that could be centralized and shared can optimize operational costs and resources. A foresight approach allows institutions to see around corners. This process must be someone’s responsibility, with an established set of reports and a regular cadence to review them.

- Finding good models: Taking the time to look at other institutions for inspiration and ideas is essential and can help create enthusiasm and generate “buzz,” such as through site visits, creating communities of practice, or simply spending time digging into other institutions’ websites. Looking outside the higher education sector can also be valuable, as other types of institutions have identified many of the same issues. While their governance structures may differ, the challenges are analogous.

- Embracing change management: Adopt a regular process for including stakeholders in the planning process, defining what’s changing, assessing their readiness for the change, and then designing and delivering change programs to support them. These might include communications through different channels, training and workshops, identifying and supporting champions, prototyping through mock-ups and skits, and rigorous pilot projects.

Making a difference

Students, faculty, and staff are changing, as are their space and technology needs. With the right roles, structures, and processes, educational institutions can close the gap between needs and facilities to more successfully align academic programs.

Doing so will be challenging but worth the effort by helping educational institutions fulfill their potential, create inclusive communities, provide inspired learning, and produce remarkable research and develop fruitful partnerships. It’s time to get to work!

Elliot Felix is a partner at Buro Happold Company and lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Elliot can be reached at [email protected]

Chris Buddle is associate provost for teaching and academic planning at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec. Chris can be reached at [email protected]

Technology + Trends

Seeks to identify technology and trends evolving and emerging in educational facilities. To contribute, please contact Craig Park, field editor of this column.

See all Technology + Trends.