“A silo is a part of a company, organization, or system that does not communicate with, understand, or work well with other parts.” — Cambridge Dictionary Online

We all know that silos impede good work and generate waste, yet they are pervasive in many bureaucratic organizations. This article discusses how low expertise within an organization creates the conditions that perpetuate silos. Expertise-driven Project Delivery (XPD) is proposed as a learning tool to help facilities managers build internal expertise and reduce the need for silos.

Silos Serve an Important Function for Senior Leaders

All organizations can suffer from a lack of internal expertise. Not everyone in an organization is good at their job. People with low expertise tend to hire more people with low expertise. Steve Jobs coined this the “bozo explosion.”

When a lack of expertise goes unchecked in one department, it begins to damage the efforts of other departments. Management becomes increasingly drawn into cross-departmental conflict. Senior leaders lose trust in each other and begin to seek ways to isolate their work from each other and their departments. Silos naturally evolve as a misguided means to contain this problem. Senior leaders build silos in the hope that they will give them enough control to do their job well with minimal disruption from other departments.

Change Won’t Begin Until the Status Quo Stops Working

“Never let a good crisis go to waste.” — Winston Churchill

Universities are organizations patterned around familiar annual cycles. Recruitment, research, accreditation, and residency all follow predictable cycles. Managing the risk in these cycles becomes routine from year to year. “Following the rules” creates predictable outcomes. This regularity gives the impression that everything is under control. The silo culture goes unchecked, and patterns of low expertise remain concealed.

Inevitably, there arrives a risk that falls outside the normal pattern. In facilities management, this risk commonly occurs on a large capital project involving many stakeholders. When the budget is suddenly exceeded or the schedule breaks, a large swath of the university’s operations is impacted. Senior leaders, including the chief executive and board of governors or trustees, become involved. People all around the university are galvanized by a common interest. They begin to question established procedures and seek alternatives. Although painful, these crises are the best opportunity to challenge the silos. Now is the opportunity to consider the root of the problem: Why are we not attracting, building, and retaining internal experts?

Expertise-Driven Project Delivery (XPD)

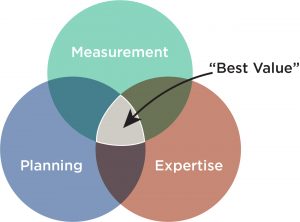

Expertise-driven Project Delivery (XPD) is a method to increase the probability of hiring the highest performing vendors (https://simplar.com/procurement-project-delivery). The root of the system is learning how to identify, attract, and manage people who are experts. The method was developed as a research project at Arizona State University in collaboration with the Simplar Institute. The process seeks to find the point of “best value” by combining planning, measurement, and expertise into a management system.

- Planning is the assembly of all the various project activities to achieve the intent within the given constraints.

- Measurement is the objective quantification of key project statistics such as cost, schedule, and scope elements (i.e., number of beds in residence or seats in a classroom).

- Expertise is the ability to identify risks and successfully mitigate them.

Most institutions already plan and measure their projects. Identifying, attracting, and managing experts is often the missing piece to finding the “best value.”

How to Identify and Attract an Expert

What do experts look like? Consider a highly skilled person that you already know, someone who does the job right without much supervision. What kind of work attracts that person? Experts often have many of these common traits:

- Experts know their work, own the end product, and view their job as highly valuable.

- Experts identify the risks before they occur and know the best ways to mitigate them.

- Experts seek work arrangements with freedom and independence.

- Experts do not like to cut corners and have contempt for poor end products.

- Experts despise being micromanaged.

One of the first learnings in XPD is how to become a client of choice for experts. To do this, the selection of vendors needs to be focused on expertise, and less on price or past relationships. XPD provides three tests to evaluate a vendor’s expertise:

- Risk: Can the expert identify the specific risks of a project and provide specific strategies to mitigate those risks?

- Value-Add: Can the expert identify specific improvements that would increase the value of the project, either by adding or deleting features or by proposing alternative methods?

- Capability: Can the expert identify specific previous experiences that directly relate to the current project and their role?

How to Manage an Expert

Having hired an expert, XPD also requires a shift in project management methods.

Successful project management utilizes measurement, planning, and expertise. Client requirements are quantified into measurable outcomes. Plans are assembled to achieve the outcomes. Experts are engaged to execute the plan.

Measurement drives planning drives expertise.

After engaging the expert, XPD reverses this process. The expert is asked to replan the project based on their understanding of the risks, value-adds, and experience.

Expertise drives planning drives measurement.

When the expertise-driven plan is approved, the role of the owner is to measure the progress of the plan. This is done using a risk register at weekly meetings. The owner’s role is to assist the expert with risks that are outside the expert’s control. The owner must provide speedy responses to requests for information and approvals. The owner must avoid directing the work or micromanaging the expert.

Identify, Attract, and Manage Internal Experts

In the same way as you evaluate your organization’s appeal to external experts, consider if your organization behaves in a way that is attractive to internal experts. Are your workers and managers selected on their ability to manage risk, add value, and apply past experience? Do you allow these experts to replan your projects? Do you measure their outcomes and provide them assistance with elements outside their control?

One practical way to start immediately is to begin by assuming all your employees are experts. Experts manage risk well, can provide specific value-adds, and successfully apply their past experience. Test this assumption by asking them to replan projects based on their understanding of risk, value-adds, and past experience. Measure the outcome of their efforts and give them assistance with risks outside their control.

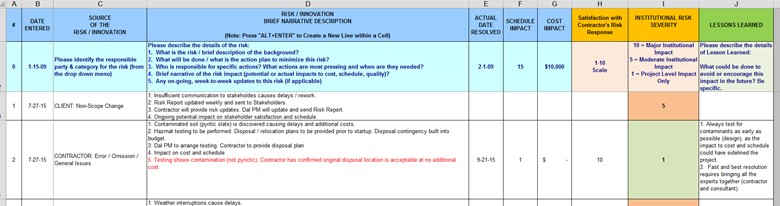

One simple method is to create a common risk-planning tool for all employees working on similar projects. This tool should measure the impact of risks and identify their sources. The tool should explain the risk, how it was mitigated, and by whom. Soon you will get a much better picture of where your risks lie and who are your internal experts.

For example, some of your employees will show an early ability to create good risk plans. They will quickly identify risks in advance and know how to control them. They will say, “This is just common sense,” or “I already do this anyway.” They will use the risk plan to leverage improvements on their projects and seek help for risks outside their control. The rate of unexpected change in their work will decrease. You will need to spend less time overseeing these employees.

You will also observe that some of your employees have difficulty identifying risks in advance. Their risk management strategies will be generalized, not project specific. Unexpected risks will continue to pop up on their projects, and they will not seek help until after a problem occurs. You will need to spend more time overseeing these employees.

Example of a risk-planning tool created in Microsoft Excel.

Case Study: Measure the Outcome

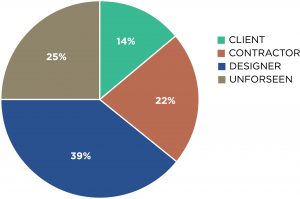

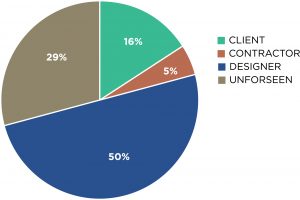

A risk-planning tool was used for two years across dozens of small-to-midsize university construction projects. Project managers identified every risk that changed the cost or schedule of their projects. Every change order was included as a risk, and the source of the change was tracked. The team expected contractor error and unforeseen conditions to be the greatest source of project risk. The process revealed a surprise: Designers contributed the greatest risk to both cost and schedule overages (see pie charts below).

The project manager’s efforts were then focused on hiring design consultants with higher levels of expertise.

Risk Sources for Change in Project Cost:

Risk Sources for Change in Project Schedule:

Conclusion

“Silo culture” is rooted in a problem of low internal expertise. Before any silos can be dismantled, the organization needs to build a culture of high expertise.

XPD provides tools to identify, attract, and manage experts. These tools can be applied to grow and encourage internal expertise.

Apply this learning back to your organization. Does your organization treat your employees as though they are experts? Can your employees manage risk, add value, and apply past experience? What if you allowed them to replan your projects? Measure their outcomes and provide them assistance when requested. The results may surprise you!

Ian Wagschal is director of facilities management at University of King’s College, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. He can be reached at [email protected]. This is his first article for Facilities Manager.

To learn more, view Ian’s presentation at APPA’s November 2021 Facilities Symposium.