How can a facility owner or project manager determine which product is best for the job, and for the budget? “Total cost of ownership, or TCO, is a holistic approach that allows owners to make the best decisions,” says Ana Thiemer, associate director of planning and project services at the University of Texas at Austin.

Richie Stever

Ana Thiemer

According to Richie Stever, director of operations and maintenance for the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC) in Baltimore and Facility Executive magazine’s Facility Executive of the Year in 2019, industrial insulation was never something his team gave much thought to. Stever characterized insulation as “set it and forget it.” However, after analyzing what reusable insulation could deliver, he determined his initial investment would help him recoup energy savings and money that he could put toward insulating additional components in his steam system, which delivers heat energy to a 2.1-million-sq.-ft. teaching hospital.

Inside TCO

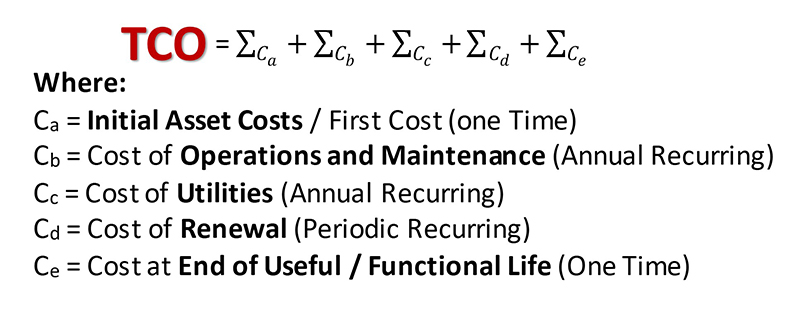

Total cost of ownership is a financial estimate, a way of predicting the economic impact of a purchase through the collection and analysis of data. Cameron Christensen, associate vice president of facilities at the Juilliard School in New York, divides the TCO formula into thirds. “The three areas are project delivery, operation and maintenance, and recapitalization,” explains Christensen.

Cameron Christensen

Project delivery comprises costs for design and engineering, production, installation, commissioning, and startup. Operation and maintenance include the cost of utilities, regulatory compliance, and safety. Recapitalization, likewise, includes renewal costs—when a system needs to be replaced or overhauled, as well as end-of-life costs for the product. “That in essence comprises the whole formula for total cost of ownership,” says Thiemer.

The basic concept of TCO is to ascertain how much each of these costs would be for a certain product, and do the same for your existing or competing systems. Once a manager compiles the data, he or she can analyze the products or systems and compare one to another to determine which is most cost-effective over time.

According to APPA, the APPA TCO-1000 standard is “a holistic approach to maximizing return on investment of managed physical assets that includes the summation of all known and estimated costs to include first, recurring, renewal/replacement, and end-of-useful life costs revised at critical decision points to aid in life-cycle asset management decisions.”

A Look at TCO’s Roots

The idea of determining the life-cycle costs of a product before making an investment was conceived in the late 1970s at Brigham Young University (BYU). “A lot of that was because of my dad, Doug Christensen. He pioneered life-cycle costing when everyone was trying to figure out preventive maintenance,” says Cameron Christensen. “I have a study he did in the ’70s that is arguably the oldest for total cost of ownership on a product selection that I’ve seen.”

Deke Smith

That study concerned what kind of flooring would be used in the chapels of BYU; Doug Christensen did an in-depth analysis of life-cycle costs to determine the most cost-effective option over 40 to 50 years into the future. He determined that carpet was the most cost-effective. “Since that study in the 1970s, chapels for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints around the world all have carpeting,” added Christensen.

“Doug Christensen, Ana Thiemer, and I started developing the APPA TCO standards,” says Deke Smith, co-chair of the APPA TCO Committee and partner, DKS Information Consulting, LLC. “Doug passed away as we were finishing part one of the standards, but we used his example for the rest of the standard.”

Why is TCO Important?

The systems that a business chooses to use can influence cashflow, public perception, and even the behavior of competitors, so choosing the most cost-effective option can be a strong asset. Unfortunately, total lifetime costs often take a backseat to upfront price when it is time to decide.

“Only 28 to 33 percent of total cost of ownership is in project delivery, yet that’s where we spend all of our time,” says Christensen. “We really look and finely tune those construction jobs, but when it comes to operation and maintenance, we let it run ragged a little bit, and that’s 40 percent of TCO.”

For example, buying an $800 bed frame that lasts 15 years is better than buying a $300 bed frame that only lasts 5. Only looking for a low sticker price might result in frequently replacing that product, which ultimately costs more than investing in a more expensive, but higher-quality product.

Two TCO Resources:

APPA TCO Full Standard — Parts 1 and 2 Combined (Key Principles & Implementation and Data Elements)

Buildings….The Gifts That Keep On Taking: A Framework for Integrated Decision Making

Facility owners can also apply TCO to existing systems. Take an HVAC system halfway through its normal service life that, due to poor design and installation, isn’t operating at full capacity and constantly needs maintenance. Using TCO, the operators of the HVAC system can determine whether it would be more cost-effective to replace the whole system or run it to failure.

“We have to account for the original cost, and what it’s costing us right now—weekly, monthly, yearly—because it isn’t operating well,” says Thiemer. “If we were to replace the system right now, would we save money? Sometimes the answer is yes.”

TCO can be applied when an institution receives something as a donation or gift. Thiemer gave the example of an educational institution being gifted a memorial fountain by a wealthy alumnus. “Wow, what a really cool thing for a university, right?” says Thiemer. “They get an attraction on campus; they know students love water features, and it makes the campus more beautiful. So, the university might say, ‘Yes, let’s do it.’”

Because the initial price to the institution is nothing, it seems a no-brainer to accept the gift. However, even a fountain recycling water will regularly lose water to evaporation, so there will be the cost of replenishing the water; energy costs to power the fountain; and regular, sometimes specialized, maintenance. The costs add up over time.

“Our initial cost is free, but if we don’t use total cost of ownership to think about the other costs, then we’ve made a decision based on only one of those costs and not the full picture,” says Thiemer.

A TCO analysis can also factor into things like energy savings when purchasing sustainable products. “Energy has led the way in TCO with things like the switch to LED lighting,” says Smith. “A 7-watt LED light, equivalent to a 40-watt incandescent lightbulb, could pay for itself in about 1,000 hours. The same concept applies to every product put in the building.”

Applying TCO

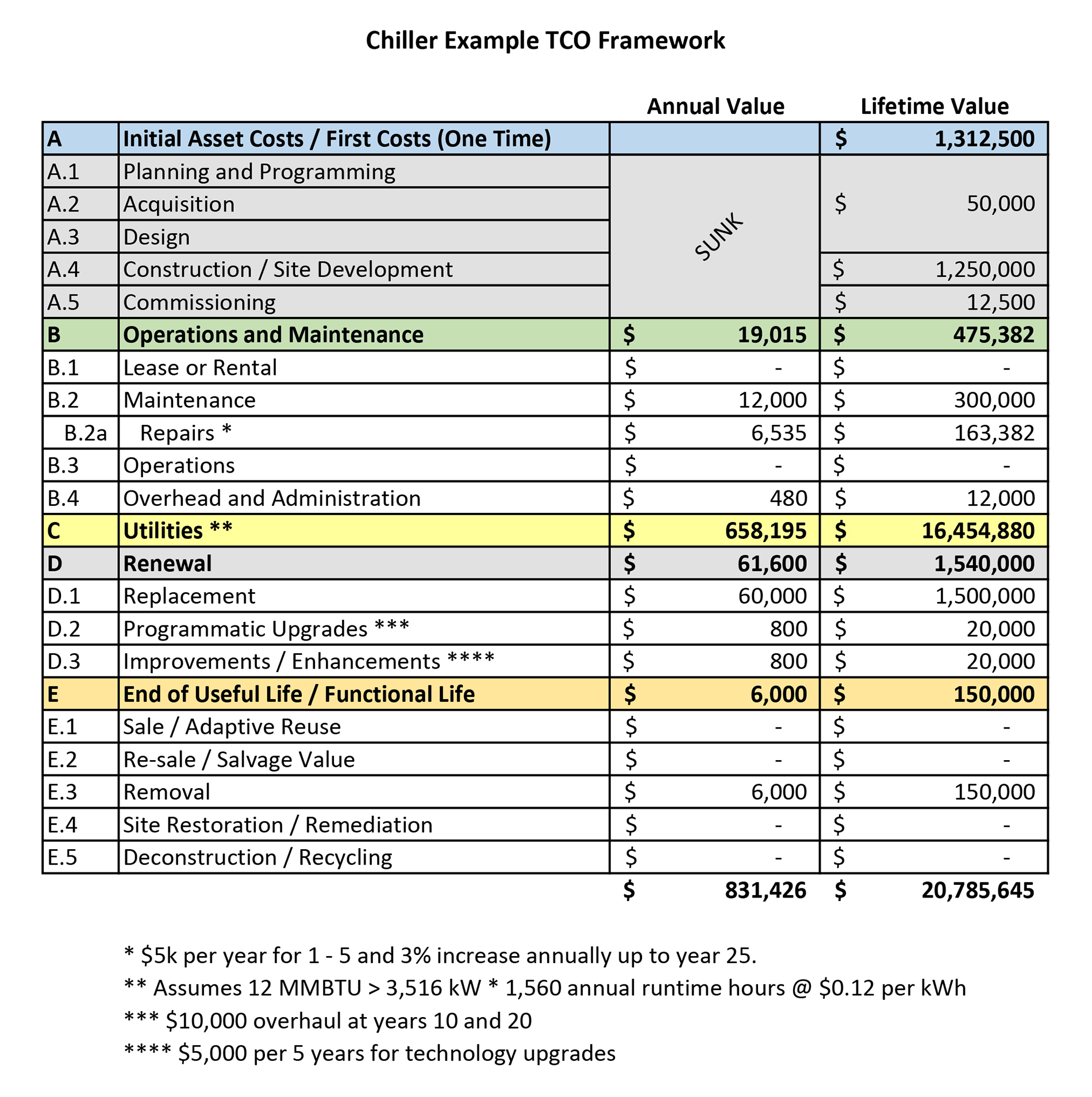

When it comes to applying total cost of ownership, the first caveat is that TCO is not always easy to ascertain. It requires data collection (Figure 1) and analysis to be effective.

Figure 1

“You don’t need to run a TCO analysis for a restroom exhaust fan. But you should do it for your chillers, boilers, central systems, and electrical switch gears,” says Christensen. When it comes to convincing someone who only looks at initial cost, Thiemer says it’s important to ensure that the decision maker has all the information to ensure the best choice is made (Figure 2).

“Calculating TCO is the best financial decision for the organization. As a whole, that’s how I would pose it,” says Thiemer.

Figure 2

The University of Maryland Medical Center Applies TCO

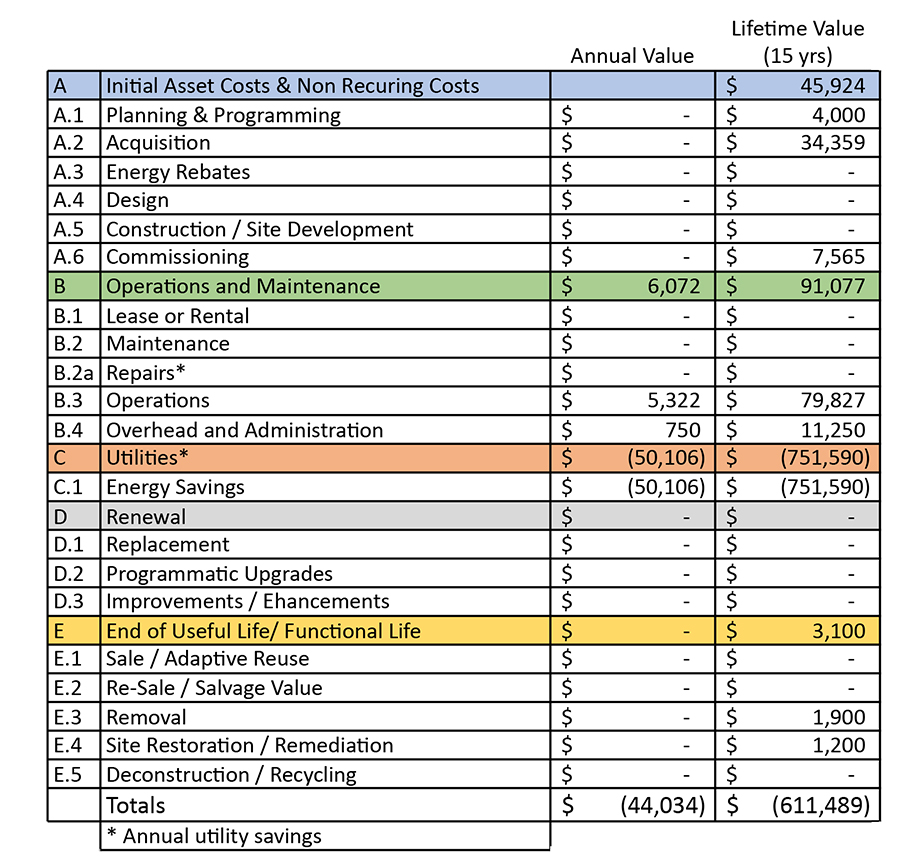

UMMC’s TCO analysis included an energy survey demonstrating that over the lifespan of the reusable insulation blankets (approximately 15 years), Stever would save $751,590 for his institution in steam costs on just 100 insulated components. With removable and reusable insulation blankets in place, he would see a heat-loss savings of 1.5 billion BTUs per year. And his project team estimated the annual emissions savings attributable to the reusable blankets to be in excess of 152 lbs. of nitrogen oxide pollutants (NOx) and more than 50 tons of carbon dioxide (CO2). For his insulation project, Stever embraced TCO and resisted the urge to simply say, “We have insulation and are in good shape” or “We don’t have the funds.”

In Figure 3, item A.1 represents planning and programming where even though the manufacturer is providing the energy conservation measure, time is still required to evaluate the proposal and obtain funding. With item A.2, or acquisition, we have the cost for the thermal blankets and installation. In item A.3, or energy rebates, this section could be combined with A.2 if energy rebates were not available for the project. In the case outlined in Figure 3, there were no rebates available.

Figure 3

For item A.6, or commissioning, the installation cost was $7,565. (Note: An escort was required to unlock and lock doors to the various mechanical rooms.) For item C.1, energy savings, thermal blankets saved $50,106 per year. Section D was not applicable to this project.

For item E.3, or removal, at the end of the blankets’ useful life, UMMC will have to remove the product, and this amount estimates the labor required. In item E.4, site restoration/remediation, UMMC provides the cost to dispose of the blankets. Since the materials are not toxic to the environment, maintenance staff can dispose of the blankets using a dumpster. This cost represents the cost for the dumpsters.

Conclusion

Facility and plant managers who rely on TCO see the payoffs several ways. First, they can back up decisions, even unpopular ones, with data. This takes the emotion or guesswork out of investments in equipment or other assets. Second, decisions based on TCO in one area by definition create opportunities elsewhere.

For instance, taking a TCO approach to buying HVAC equipment might mean a larger initial investment for more dependable machinery. But the long-term picture may translate into quarterly savings that a facilities manager can apply elsewhere for other equipment purchases, repairs or maintenance. In other words, with TCO, a facilities manager’s decisions aren’t viewed as isolated, siloed ones. A decision made with TCO in mind pays dividends, in most cases, for years to come.

Joe Lauria is vice president and chief operations officer at Shannon Global Energy Solutions, North Tonawanda, NY. He can be reached at [email protected]. This is his first article for Facilities Manager. Additional assistance was provided by Bill Perry.

For more information about total cost of ownership, visit the APPA TCO 1000 webpage.