This column has focused on non-fiction—frequently technical—books. This selection for this issue, however, is a deviation from that pattern, as it is historical fiction. While probably a little late for summer reading lists, it may be a nice diversion for some readers.

As an additional note, this column welcomes guest book reviews. Advance permission is not needed, simply submit to the editor. There are some great books and readers in APPA, this is an outlet to share what is available.

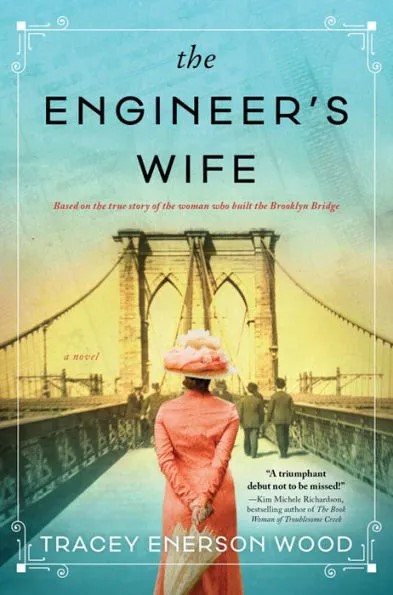

The Engineer’s Wife

Wood, Tracey Enerson, Sourcebooks, Naperville, IL, 2020, 384 pages, e-book, $10, softcover, $12, hardcover, $18.

The Brooklyn Bridge has retained its iconic status since it opened in 1883. How did it become iconic and how did it come into being? It didn’t happen without the dedicated involvement of The Engineer’s Wife, Emily Warren Roebling, as described in an historic novel.

The Brooklyn Bridge has retained its iconic status since it opened in 1883. How did it become iconic and how did it come into being? It didn’t happen without the dedicated involvement of The Engineer’s Wife, Emily Warren Roebling, as described in an historic novel.

The Brooklyn Bridge was conceived by John A. Roebling, a German immigrant to the United States who was a talented engineer and entrepreneur. The bridge was not a one-off creation, several other bridges preceded it— an aqueduct bridge over the Delaware River, a two-level bridge at Niagara Falls for both carriages and trains, one in Pittsburgh over the Allegheny River, and the Cincinnati-Covington Bridge. Each bridge was longer than the previous one. Roebling’s son, Washington, helped with the construction of bridges in Pittsburgh and Cincinnati after completing his civil engineering degree from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI), and was planning to assist his father with the Brooklyn Bridge. All this would have worked well, but John got tetanus and died following an injury that occurred while surveying for the bridge. He handed off construction of the bridge to Washington.

A critical part of any bridge construction is the development of the foundation to hold the bridge and carry the loads of users. The Brooklyn Bridge required the foundation to be constructed in the river. This required the construction of caissons, which were sunk in the river, and men were required to work inside the caisson to excavate from the riverbed to the bedrock beneath. The caisson excavation required increasing air pressure to hold out the water, a technique used previously in Europe and in St. Louis for the Eads Bridge. Working in this high-pressure environment resulted in what was called caisson disease (also known as decompression sickness or “the bends”), an affliction caused by rapid decompression at the end of the work shift. Washington frequently inspected the work in the caisson and became disabled with the disease, and thus unable to provide on-site supervision. Enter Emily, The Engineer’s Wife. She quickly assumed significant business and technical responsibilities—first as a messenger, then with coaching and learning through engineering books—which was unheard of at a time when women didn’t have the right to vote.

The Engineer’s Wife fills in many personal details in the historical record but maintains a predominately accurate description of what occurred with the bridge construction. The personal details, family life, and relationships with others in Brooklyn at the time are fabricated to weave a compelling story for non-engineers. These include relationships with P.T. Barnum, assistance from the Rev. Henry Ward Beecher, and participation in the suffrage movement.

What was more interesting, but fabricated, were descriptions of her work in the caissons—at the top of the towers, and anchorages. The author does a good job of describing the conditions during the excavation and resolving the damage from a fire that broke out in the Brooklyn caisson. The fire and subsequent damage had the potential to ruin the project, if not addressed correctly. Missing, at least to this reader’s satisfaction, was the investigation into the bad wire installed in the main cables. The detective work was mostly due to an anonymous tip about midnight activities. While this may well have been the case, the logical steps to determine what was really happening with the wire was more important.

Overall, this book is an easy read. It provides a reasonable portrayal about the construction of the biggest engineering project of the time, and the interpersonal issues associated with a woman working outside of typical responsibilities near the end of the 19th century. While Emily Warren Roebling demonstrated the knowledge and skills of an engineering graduate through the bridge construction, it wouldn’t be until World War II when women were admitted to RPI, and almost 100 years after the bridge opened would women comprise significant numbers at RPI, where her son graduated in 1857.

While not a typical read for the facility engineer, The Engineer’s Wife may be a good book to entice a young woman who is thinking about a career in engineering.

APPA Fellow Theodore (Ted) Weidner, PhD, PE, RA, NCARB, DBIA, CEFP, is professor of engineering practice at Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana. He can be reached at [email protected]. If you would like to write a book review, please contact Ted directly.

Bookshelf

Book reviews on current publications relevant to the profession, trends, and working environment of facilities and educational managers and professionals. To contribute a book review, contact Ted Weidner, field editor of this column.

See all Bookshelves.