Within the boundaries of building facility programming, users and design teams often focus on the assignable spaces that represent a person, entity, or specific programmatic function. After program requirements have been defined in real terms, the specific square footage values are increased by a grossing factor to ensure enough total space is included to accommodate necessary circulation space, assign building support, and define transition space around and between suites and departments. Although a strong program of requirements and building efficiency is a fundamental best practice to drive building projects forward with some cost certainty, this program does not encompass all possibilities that can be achieved quantitatively. Critical thinking should be placed on the campus’s qualitative goals, alignment with the master plan, engagement of mission, and solutions to improve workspace or culture, which can prompt inclusion of open or unassigned spaces. A good practice is to engage in a deep roundtable discussion before programming begins to define what is required for a project to be successful.

Many times, users and clients state nothing about the needs of their personalized space, becoming more aware of opportunities when they hear their colleagues state what matters to them. Brian Roeder with Page/, a full-service design, architecture, and engineering firm, notes that higher education facilities programming goals are often centered on faculty culture, wellness, retention, creative engagement, student success, research/teaching on display, and partnering. To emphasize the importance of these goals, architects promote collaboration and the chance opportunities afforded by open spaces over multiple stories in campus buildings. These are known as communicating spaces, sometimes called “mini-atriums.” These spaces can be fundamental building blocks for engaging faculty, staff, and students in collective communities. By setting up success goals at the front of building planning, project leadership can embrace and understand the value of communicating spaces in driving mission and supporting collaborative engagements for building users. Conformance with applicable codes keeps that openness in check and ensures life safety requirements are maintained.

Code compliance for communicating spaces

A two- or three-story vertical opening does not necessarily need to be classified as an atrium, which can require a smoke control system. An alternative in the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 101-2021 edition, is included in Section 8.6.6 – Communicating Spaces. This option that does not require the design, installation, and maintenance of a smoke control system; and the 2021 edition of NFPA 8.6.6 (3)(b) allows for communicating spaces to have automatic smoke detection in lieu of a readily obvious view of any part of the communicating space for the occupants of the space.

Some occupancies specifically allow communicating spaces; some, for example new/existing health care occupancies, prohibit communicating spaces per 18.3.1.6 and 19.3.1.6. Michelle Gebhart, with Jensen Hughes fire protection engineers, was contacted for this article. Michelle confirmed that, in a fully sprinklered building, a communicating space may connect up to three contiguous stories when the building or occupant characteristics comply with all of the following provisions:

- The lowest or next-to-lowest level egresses directly to street level.

- Contents are restricted to ordinary hazards.

- The space is separated from the remainder of the building by smoke barriers.

- Sufficient egress capacity enables all occupants of all levels served by the communicating space to egress simultaneously.

- Occupants within the communicating space have access to at least one exit without having to traverse another story within the space.

- At least one exit is available to occupants not in the communicating space without them needing to travel through the space.

- The space provides a high level of awareness by either being open (with clear line of sight) and unobstructed or open and is provided with smoke detection.

By meeting all the criteria in Section 8.6.6, a building with the allowed occupancies may contain up to a three-story vertical opening without smoke control when NFPA 101 is the adopted code.

Operations and integrated system testing

However, when smoke control systems are required for interior open spaces, successful integrated system testing must be achieved before activating the building and occupying the spaces. Moreover, this test must be repeatable with all components working individually and as part of the overall system as designed and commissioned. After the building is accepted and occupancy is achieved, systems that require the fire control panel, fire alarm, HVAC controls, actuators and dampers, and exhaust and smoke evacuation systems to work effectively together to reduce smoke accumulation in a fire or similar event must be reliable and continue to meet their required performance standards.

A Texas close-up

For public buildings in Texas, the state fire marshal is the authority having jurisdiction for life safety, and the state fire marshal’s office adopts NFPA codes on behalf of state agencies. NFPA 4 is required by the 2021 editions of both NFPA 1 and NFPA 101. Operations and maintenance teams must ensure compliance for existing systems, and design and construction teams must address compliance for any new projects. Because of the requirement for integrated testing, teams need to consider performance outcomes very early in the planning process for buildings proposed to include smoke management systems or that are classified as “high rise.” If that code requirement constrains the architect’s desired level of openness, the team has to adjust. From an owner’s perspective, it is best to address this completely in design and not wait until the later stages of construction or at substantial completion, when the NFPA 4 test will help confirm successful achievement of design intent and the building can transfer from contractor to owner.

For all existing high rises and installed smoke management systems in Texas, NFPA 4-2021 includes a retroactive requirement for integrated system testing within five years of code adoption (in Texas, that is August 31, 2028). When contacted on this topic, John DeLaHunt, assistant director and fire marshal at the University of Texas at San Antonio, advised, “All involved will feel the greatest influence of NFPA 4 after each component is built and individually tested, coincident with final commissioning prior to substantial completion. This is the single moment of greatest scrutiny, and everything depends on these components working together as a system—exactly as we would expect in a real building emergency.”

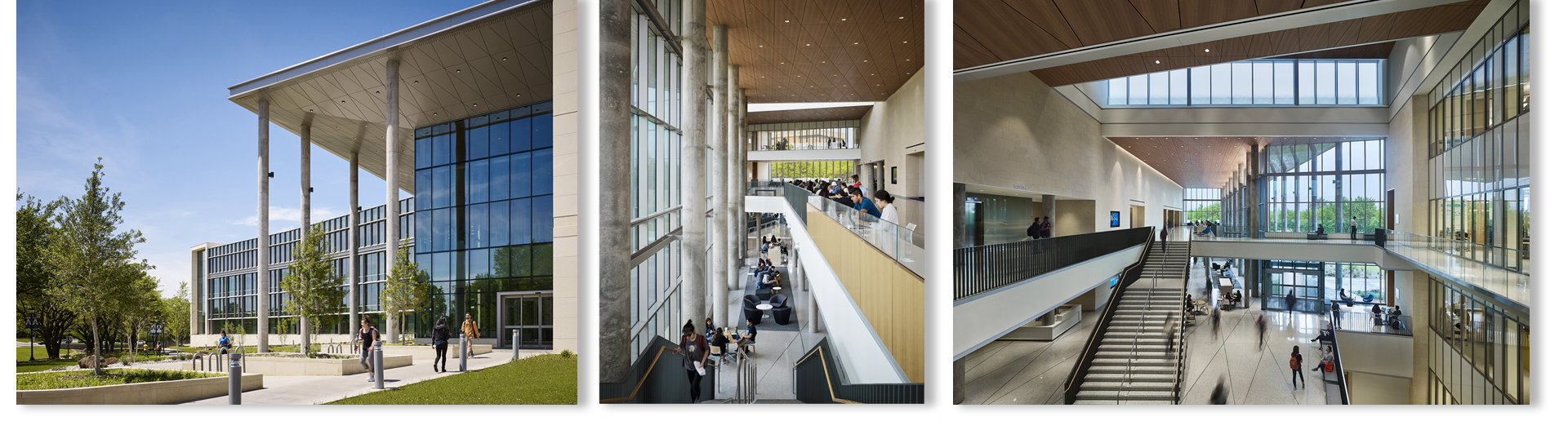

The University of Texas at Arlington, Science and Engineering Innovation and Research Building

Page in association with ZGF, 2018, used with permission. Photo credit: Nick Merrick © Hall+Merrick

Stephen Harris is assistant vice chancellor for capital projects at the University of Texas System in Austin, Texas. He can be reached at [email protected]. The following individuals also contributed to this column: Brian Roeder, Page/, Michelle Gebhart, Jensen Hughes; Doug Powell, UT System; Yashambari Ajinkya, UT System; John DeLaHunt, UT San Antonio.

Code Talkers

Code Talkers: Highlights the various codes, laws, and standards specific to educational facilities and explains the compliance issues and implications of enforcing these measures. To contribute, contact Kevin Willmann, FM Column Editor.

See all Code Talkers.