Change and expectations of change are increasing exponentially, especially with websites and email that encourage demands for timely information. This is true for universities as a whole and for facilities departments. Organizational and individual change management provide a structured basis for effective change, so facilities managers must anticipate obstacles and resistance to change, serve as leaders for change, focus obsessively on quality, and encourage teamwork.

Leading Change

View facilities leaders as change agents. Facilities managers must understand the difference between change management (climbing the ladder) and change leadership (determining whether the ladder is leaning against the right wall, leading the charge to move or strengthening the ladder). Change agents fill numerous roles, including director, coach, caretaker, interpreter, nurturer, and motivator. They must enlist the support and active participation of top and mid-level managers to ensure quality. To avoid the biggest mistake they can make, change agents must create the sense of urgency needed to overcome organizational inertia. Change agents must be committed to long-term change management and creation of a culture of change; organizations cannot abandon change in mid-stream or fail to follow through on initial successes without risking a greater resistance to change in the future.

Define a strong and sensible vision. Effective change leaders start with the end in mind to avoid going in the wrong direction (or no direction at all). A strong vision serves three functions: setting the general direction for change, motivating people to take action in the right direction, and helping to coordinate actions of different people. A clear and effective vision has six characteristics (picture of the future, set of possibilities, long-term interests, realistic and obtainable goals, clear and focused vision, flexible vision, and easily communicated vision). Leaders then develop a rough road map for implementation, conduct a collective dialogue to consider effectiveness and efficiency questions, and develop shared organizational vision by using methods such as strategic planning and sensing sessions.

Communicate the vision. Change leaders obtain buy- in, disseminate the vision, and create emotional acceptance. Some people automatically buy in to the vision, but most do not commit, and some resist immediately. Therefore, effective communication of the vision must use clear, concise, and easily understood terms in multiple and different forums and formats to reach as many people as possible and repeat the message until it is heard. One powerful form of vision communication is leading by example (especially top leaders). Change leaders also must actively solicit feedback and cultivate the trust of other people by demonstrating personal integrity and concern for the best interests of the organization.

Create short-term wins. Time is needed to implement incremental change and see measurable results (4 to 6 years), but sustaining necessary effort is difficult unless people see results in 6 to 18 months. Short-term wins can show people improvements, include small celebrations to motivate continued efforts, offer an opportunity to assess and refine the change process, and share momentum to attract more support, but such wins must be balanced against the need for an ongoing sense of urgency to drive change.

Develop strong coalition. Powerful force is required to establish and sustain a change process. Teams can help change agents in developing and communicating the shared vision, eliminating key obstacles, producing short-term wins, directing multiple change projects, and anchoring cultural change. However, for teams to be effective, organizations must reward individuals for team performance; managers must be encouraged to promote team decisions; teams must be trained in effective decision-making; and leaders must instill a sense of mutual trust among teammates and develop strong common goals.

Understand workforce culture. The organization’s workforce culture is complex, influential, and often the biggest roadblock to change (“that’s not the way things are done around here”). Nonetheless, it can be changed (as a recent experiment with monkeys clearly illustrates). However, change leaders need to be patient and persistent as the organizational culture slowly (and initially unevenly) embraces change; they need to recognize that the organization has values that reach deep and integrate into a network of beliefs that tend to support the status quo.

Manage resistance to change. Transitioning to the unknown creates natural resistance and triggers an innate fight-or-flight response. Resistance to change can be evidenced by how people feel about the change, how they think about it, and how they act in the face of change. Change agents should be able to recognize each, understand signs and causes, and guide change as needed. People resist change for many reasons (e.g., personal concerns, organizational culture, or poor previous experiences with change).

Change is situational and external and thus different from transition, the internal psychological process that people use to come to terms with a new situation.

Effective change leaders allow time for transition, which is essential for permanent change. The three-step transition process is based on (1) denial and resistance,

(2) exploration of possibilities while still neutral (the most difficult and confusing step), and (3) acceptance and commitment. In the first step, change leaders overcome cultural inertia by expecting, accepting, but not overacting to subjective needs to grieve loss of the past; communicating the new vision and a sense of urgency; and anticipating who will be affected by rippling effects of change. In the second step, change agents manage the process so that change works; the organization is intact; and time is saved in the long run. They might wait out this step for small changes, but large changes need support such as giving everyone

important roles, creating transition theme, emphasizing short-term wins, communicating clearly, implementing support systems, and cultivating trust. However, abandoning the change midstream is worse than not starting. In the third step, change agents reinforce a culture of change by publicizing and celebrating successes every step of the way, explaining any changes to the process (and using employee feedback as input), and recognizing employee contributions. To promote a culture of continual improvement, change leaders must continually guide the organization through the three-step transition cycle, but organizations can quickly become comfortable with the new process.

Implementing Change

Quality leadership improves how (not what) work is done, including emphasizing customer needs, focusing obsessively on quality, supporting ongoing learning, creating and refining work processes and metrics, encouraging teamwork and common goals, and promoting continuing training and education. One method for implementing quality leadership is the Joiner Triangle.

Define quality. In process improvement, each person in an organization has suppliers (people or organizations that precede the process being studied) and customers (those that follow the process), so quality is part of each step of the process, starting with the customer and including collaboration with suppliers and customers.

Responsibility ultimately rests with top managers, who establish and reinforce a commitment to quality. To successfully compete with outsourcing, facilities departments need to aspire not just to customer satisfaction but to customer delight, seek opportunities to improve, and implement communication processes to include suppliers, customers, and feedback in the facilities change process.

Apply the scientific method. A series of tasks is a process, and a series of processes is a system. When work is viewed as a series of processes, people understand how input quality largely determines output quality and how their roles contribute to the entire process and to the final product. Process improvement teams should focus on one process at a time (unless processes are closely related).

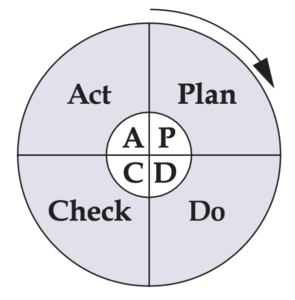

The scientific method, a systematic approach to studying processes, can be complicated but more often is a simple way for teams to study root causes and quality improvement methods. At least 85 percent of problems can be corrected by management improving processes, but only 15 percent are under employee control (including ones stemming from poor instructions or inadequate training). Evolving since 1620, the scientific method includes the current Plan, Do, Check, Act (PDCA) approach; relies on iterations to add knowledge and incrementally improve the next PDCA cycle; and typically is used in quality control (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Plan-Do-Check-Act Cycle (also known as the Shewhart Cycle, Plan-Do-Study-Act Cycle, and Deming Cycle or Wheel)

Employ quality management methods. The PDCA check phase uses a large number of established quality management methods to analyze and enhance organizational performance. The more common tools include flowcharts, Pareto charts, cause-and-effect diagrams, time plots, control charts, dot plots, scatter diagrams, and scatter diagrams.

Apply process improvement methodologies. PDCA allows major performance improvements and frequent incremental improvements. The PDCA cycle can be implemented by using one of a number of methodologies, such as Lean production (based on the pull system and value stream mapping), Six Sigma (and its two key methodologies, DMAIC and DMADV), Japanese-rooted kaizen continual improvement approach, and business process improvement (which focuses on radical change in organizational performance rather than a series of incremental changes).

Create project teams. Teams enable leaders to pool skills and obtain major and synergistic improvements in quality and productivity, but teams pose a number of complicated managerial and interpersonal issues. The time needed to complete the four stages of team creation (forming, storming, norming, performing) depends on the experience of the team members.

Leaders must recognize that these stages are normal and necessary and not disband the team before it completes them, thus impeding future efforts.

Use tools to make team decisions. Leaders must understand and manage teamwork ups and downs. Teams and leaders must be patient and persistent. Focusing team efforts can be challenging, so teams often use tools such as brainstorming, multivoting (Pareto voting), and the nominal group technique.

Apply the scientific method to solve problems. Teams need to understand the process; collect meaningful, consistent, and stable data; identify root causes of problems; develop appropriate data-driven solutions, including alternative solutions; and implement effective changes.

Identifying Trends

To foster continual improvement, teams update records and monitor metrics such as facilities inspections, financial reports, operating costs, staffing ratios, utility data, and process KPIs. Team members should remain current by networking with peers (e.g., via APPA). More formal tools for internal and external assessment of status include (1) Balanced Scorecard (BSC), which measures progress in key areas against the strategic plan; (2) internal and external benchmarks and financial and nonfinancial KPI metrics; (3) APPA Facilities Performance Indicators (FPI) survey; (4) assessment programs designed for facilities management organizations to guide the change process, such as the APPA Facilities Management Evaluation Program (FMEP), Reliability Management Group framework (Wheel), and Sightlines’ Return on Physical Assets process.

Sustaining Change

One of the biggest challenges in the change process is to sustain a change culture. For an organization to adopt a change culture it must cease seeing change as a transitory practice; change must become the norm. In a sustained change culture, people no longer label the process as “change,” which comes with all the normal resistance inertia related to change.

Create an Account

Create an Account

Login/myAPPA

Login/myAPPA

Bookstore

Bookstore

Search

Search  Translate

Translate

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.